Antonino Salinas (Palermo, November 19, 1841 – Rome, March 7, 1914) was an archaeologist, numismatist and Italian rector

Born in Palermo in 1841, Antonino Salinas began to nurture an interest in art and antiquities from his early childhood, through the influence of his mother, Teresa Gargotta, a highly cultured woman, who was educated in various subjects, including philosophy, languages, numismatics and the natural sciences.

He was educated as a young man by strict methods of scientific research, in 1856 he enrolled in the Faculty of Law at the Royal University of Palermo. After landing at Marsala di Garibaldi, he enlisted in the southern army and on July 13, 1860 he was appointed an artillery subordinate, fighting at Volturno and Capua and was dismissed in January 1861, being decorated the following year with a bronze medal. He returned to work in the Great Archives of Palermo. In those years he published his first writings about numismatics, his great passion.

In 1856, before archaeological studies were organised into the professionally oriented courses of today, Salinas graduated from the Royal University of Palermo in Law, and then obtained a position as a diplomatic historian at the Great Archive of Palermo. Between 1862 and 1865, he travelled around Europe, thanks to study leave and support from the Minister of Education, Michele Amari.

The numerous cities he visited included Berlin, Athens, and London. Abroad, Salinas was able to broaden his knowledge of archaeological excavation techniques and meet eminent scholars considered as the founders of the history of antiquity as a science, such as Theodor Mommsen.

In 1862, for one year, he was able to complete his education at the University of Berlin following the courses of archaeologist Eduard Gerhard, cartographer Heinrich Kiepert and historian Theodor Mommsen.

Salinas was appointed as Associate Professor of Archaeology in Palermo in 1865, the first teacher in the Kingdom of Italy to hold this position. He believed in the need for close and intensive collaboration among scholars in order to ensure an effective advancement of knowledge, and saw continuous dialogue between teachers and students as the lifeblood of a subject.

National Museum

From 1873 until the end of his life in 1914, he was director of the National Museum of Palermo. His idea of a museum was extremely ahead of its time: “according to my concept, a museum must be a school; if they want to make it a prison for monuments, they should buy locks and call a good gaoler…” The merging of the preservation of artefacts and education is at the core of his exhibitive philosophy: “…museums that are not kept in constant relation with teaching are more conducive to vain pomp than to truly useful instruction…”

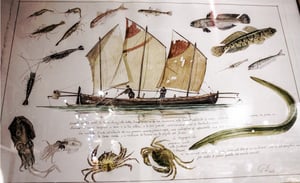

As director of the National Museum, supported by his intense collaboration with Michele Amari, an Arabist and expert on the Islamic presence in Sicily, he devoted himself with passion and perseverance to the collection and tireless study of a remarkable number of Islamic artefacts, with the intention of setting up an “Arab Room” in Palermo. On 14 April 1874, Salinas wrote to Amari: “…we have the right to have an Arab room in the Museum of Palermo and we shall have it.”

Archaeology in the field

In addition to his university assignments and administration of the Museum of Palermo, he served as director of the Superintendency of Antiquities for the region of Sicily. He played a central role in all the major archaeological discoveries of the time, directing both programmed and spontaneous excavations. His first essays paved the way for subsequent systematic research.

He participated in the excavations that took place at that time in Sicily as Mozia, Tindari and Selinunte, where he found four archaic metopeas, who moved to the National Museum of Palermo, which he directed for 40 years, until 1914. In 1907 he was appointed Superintendent for provinces of Palermo, Trapani, Girgenti and Messina. He has to find many works of art that he recovered after the 1908 earthquake of Messina. He was among the founders of the Italian Institute of Numismatics, and he was president since 1912 to death.

His investigations covered the entire island, from Salemi, Solunto and Palermo to Taormina and Tindari, and from Selinunte to Lilybaeum (now Marsala) and Mozia.

The explorations unearthed sculptures, architectural structures, coins, jewellery and inscriptions of various eras, from prehistory to the Middle Ages.

Each individual object was seen as essential for understanding the history of the civilisations of ancient Sicily. Salinas documented the findings and excavation work with precision and scrupulousness.

Salinas and archeological photography

From the time of its invention, photography was put to immediate use in archaeology and art. In the last decades of the 19th century, the development of photographic techniques contributed to a more widespread use of photography, also in the field of archaeology. Many archaeological expeditions, organised by various European institutions, began to regard the presence of a professional photographer as a part of the team. Salinas was certainly the first in Sicily to understand the potential of photography as a support for archaeological investigation, useful not only for artistic knowledge of the monument, but also as an impartial tool for the documentation of finds and monuments.

His intense photographic activity was concentrated over a period of time ranging from 1886 to 1913, and produced approximately 3,000 images. He approached photography with scientific rigour and method, as seen from the manuals of photographic technique in his library, taking notes in his notebooks on the photographs taken, lighting conditions, the type of camera used, lenses, exposure, development formulas, etc.

He was aware that photography provided a suitable tool, not only for documenting works of art, but also for protecting them.

In a letter addressed to the Ministry on the results of the excavations at Selinunte in 1893, he states: “…After the delivery of the objects to this museum, I will send the Ministry a final report accompanied by the photographs that I have taken.”

Although he was not a professional, his images show an adequate and appropriate choice of view point, framing and lighting to enhance the subject and material.

Salinas the photographer

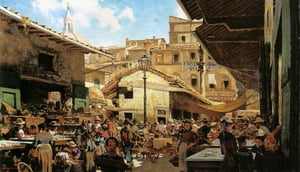

Despite the fact that his activity was for purposes of documentation, Salinas’ photographic collection also reflects the view point of an amateur photographer, allowing whatever catches his attention most to show through.

Salinas’ photographic archive is sometimes the only surviving record of his excavations, the results of which were not always published, and it preserves people, himself and the daily work for posterity.

The photographs of characters in traditional costumes, of which he was a tireless collector, show his ethnographical interests as a realist.

The desire to portray human attachment to the remnants of the past is clearly seen in many of his pictures. Salinas felt a strong desire to recover the past as a collective memory in order to build the future.

His perspective is like that of a traveller, capable of recording details that might escape the direct perception of the observer. Photographs taken during excursions, often with a familiar subject, allow us to appreciate landscapes that have now been transformed by human activity.

Motya

Perhaps some of the most moving images of Motya reveal his love for the island, where he was a frequent guest of Joseph Whitaker, member of a rich family of British entrepreneurs who produced Marsala wine and owner of the island. In 1906, Whitaker started a season of archaeological excavations on the island “under the supervision of the State in the person of Professor Antonino Salinas”.

Salinas declared in the island’s Visitor’s Book that he had been “a Moytian since 1855”.

The landscape

Lighting is the primary factor to fully capture the structures of buildings, and Salinas seems to have understood this, selecting different lighting conditions depending on the subject, in order to accentuate or attenuate the contrast on the monument, and examining and analysing the specific documentation requirements.

His images of the symbolic monuments of antiquity find fitting commentary in the romantic thoughts of contemporary and earlier European travellers.

“The temple of Segesta seems to have been placed at the foot of the mountain by a genius to whom the only point in which to erect it was revealed. It alone animates the vastness of the landscape, which it vivifies and divinely enhances” (Guy de Maunpassant).

A century earlier, reaching Taormina on 7 May 1787, J.W. Goethe wrote: “Whatever natural form it had, art has contributed to make it a semi-circular theatre for spectators. […] Sitting higher up, where the members of the audience once sat, it has to be said that never, perhaps, has a theatre audience beheld such a sight before it.”

The exhibition was prepared in collaboration with the Historical Photographic Archive of the “A. Salinas” Regional Archaeological Museum in Palermo.

The texts refer to the publication and the following reference bibliography:

“Del Museo di Palermo e del suo avvenire: Il Salinas ricorda Salinas, 1914-2014”: Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo 8 July – 4 November 2014 edited by F. Spatafora and L. Gandolfo, Palermo, Region of Sicily.