Fashion in fourteenth-century Europe was marked by the beginning of a period of experimentation with different forms of clothing. Costume historian James Laver suggests that the mid-14th century marks the emergence of recognizable “fashion” in clothing, in which Fernand Braudel concurs. The draped garments and straight seams of previous centuries were replaced by curved seams and the beginnings of tailoring, which allowed clothing to more closely fit the human form. Also, the use of lacing and buttons allowed a more snug fit to clothing.

In the course of the century the length of female hem-lines progressively reduced, and by the end of the century it was fashionable for men to omit the long loose over-garment of previous centuries (whether called tunic, kirtle, or other names) altogether, putting the emphasis on a tailored top that fell a little below the waist—a silhouette that is still reflected in men’s costume today.

Men’s clothing

Besides cloves of the mantle covering the whole body, cloaks of side type and crochet type are prevalent in knights.

A hat with a brim protruding forward in a hemispherical shape called Shuple is in fashion. Brooch with a circle of gems called Afik is used as a hat decoration, called an ansune. Other bird’s feathers were prevalent, especially the ostrich feathers were trading at high prices. Also, crown-shaped decorations wearing directly on the head or over the hat are referred to as Chapelle (undecorated) Tressoire (decorated one).

Shirt, doublet and hose

The innermost layer of clothing were the braies or breeches, a loose undergarment, usually made of linen, which was held up by a belt. Next came the shirt, which was generally also made of linen, and which was considered an undergarment, like the breeches.

Hose or chausses made out of wool were used to cover the legs, and were generally brightly colored, and often had leather soles, so that they did not have to be worn with shoes. The shorter clothes of the second half of the century required these to be a single garment like modern tights, whereas otherwise they were two separate pieces covering the full length of each leg. Hose were generally tied to the breech belt, or to the breeches themselves, or to a doublet.

A doublet was a buttoned jacket that was generally of hip length. Similar garments were called cotehardie, pourpoint, jaqueta or jubón. These garments were worn over the shirt and the hose.

Tunic and cotehardie

An overgown, tunic, or kirtle was usually worn over the shirt or doublet. As with other outer garments, it was generally made of wool. Over this, a man might also wear an over-kirtle, cloak, or a hood. Servants and working men wore their kirtles at various lengths, including as low as the knee or calf. However the trend during the century was for hem-lengths to shorten for all classes.

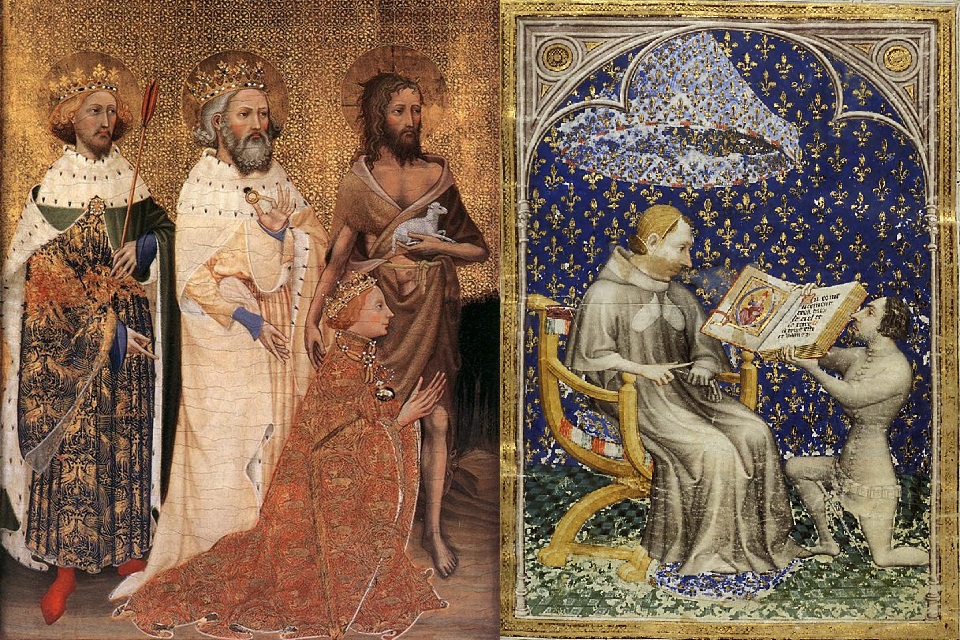

However, in the second half of the century, courtiers are often shown, if they have the figure for it, wearing nothing over their closely tailored cotehardie. A French chronicle records: “Around that year (1350), men, in particular noblemen and their squires, took to wearing tunics so short and tight that they revealed what modesty bids us hide. This was a most astonishing thing for the people”. This fashion may well have derived from military clothing, where long loose overgowns were naturally not worn in action. At this period, the most dignified figures, like King Charles in the illustration, continue to wear long overgowns—although as the Royal Chamberlain, de Vaudetar was himself a person of very high rank. This abandonment of the gown to emphasise a tight top over the torso, with breeches or trousers below, was to become the distinctive feature of European men’s fashion for centuries to come. Men had carried purses up to this time because tunics did not provide pockets.

The funeral effigy and “achievements” of Edward, the Black Prince in Canterbury Cathedral, who died in 1376, show the military version of the same outline. Over armour he is shown wearing a short fitted arming-coat or jupon or gipon, the original of which was hung above and still survives. This has the quartered arms of England and France, with a rather similar effect to a parti-coloured jacket. The “charges” (figures) of the arms are embroidered in gold on linen pieces, appliquéd onto coloured silk velvet fields. It is vertically quilted, with wool stuffing and a silk satin lining. This type of coat, originally worn out of sight under armour, was in fashion as an outer garment from about 1360 until early the next century. Only this and a child’s version (Chartres Cathedral) survive. As an indication of the rapid spread of fashion between the courts of Europe, a manuscript chronicle illuminated in Hungary by 1360 shows very similar styles to Edward’s English version.

Edward’s son, King Richard II of England, led a court that, like many in Europe late in the century, was extremely refined and fashion-conscious. He himself is credited with having invented the handkerchief; “little pieces [of cloth] for the lord King to wipe and clean his nose,” appear in the Household Rolls (accounts), which is the first documentation of their use. He distributed jewelled livery badges with his personal emblem of the white hart (deer) to his friends, like the one he himself wears in the Wilton Diptych (above). In the miniature (left) of Chaucer reading to his court both men and women wear very high collars and quantities of jewellery. The King (standing to the left of Chaucer; his face has been defaced) wears a patterned gold-coloured costume with matching hat. Most of the men wear chaperon hats, and the women have their hair elaborately dressed. Male courtiers enjoyed wearing fancy-dress for festivities; the disastrous Bal des Ardents in 1393 in Paris is the most famous example. Men as well as women wore decorated and jewelled clothes; for the entry of the Queen of France into Paris in 1389, the Duke of Burgundy wore a velvet doublet embroidered with forty sheep and forty swans, each with a pearl bell round its neck.

A new garment, the houppelande, appeared around 1380 and was to remain fashionable well into the next century. It was essentially a robe with fullness falling from the shoulders, very full trailing sleeves, and the high collar favored at the English court. The extravagance of the sleeves was criticised by moralists.

Headgear and accessories

During this century, the chaperon made a transformation from being a utilitarian hood with a small cape to becoming a complicated and fashionable hat worn by the wealthy in town settings. This came when they began to be worn with the opening for the face placed instead on the top of the head.

Belts were worn below waist at all times, and very low on the hips with the tightly fitted fashions of the latter half of the century. Belt pouches or purses were used, and long daggers, usually hanging diagonally to the front.

In armour, the century saw increases in the amount of plate armour worn, and by the end of the century the full suit had been developed, although mixtures of chain mail and plate remained more common. The visored bascinet helmet was a new development in this century. Ordinary soldiers were lucky to have a mail hauberk, and perhaps some cuir bouilli (“boiled leather”) knee or shin pieces.

Braies are worn rolled over a belt at the waist. Catalonia.

Shirt is made of rectangles with gussets at shoulder, underarm, and hem.

Serving man wears a knee-length tunic with long, tight sleeves over hose. Wears a belt with a waist-pouch or purse. His shoes are pointed. From the Luttrell Psalter, England, c. 1325–35.

Bridegroom wears a red cotehardie, hose, and hood, Italy, 1350s.

Man in a particolored cotehardie of reddish brown and plaid fabric, 2nd half of the 14th century, Catalonia. The cotehardie fits snugly and is buttoned up the front. A narrow belt is worn around the hips.

Huntsman wears side-lacing boots, late 14th century.

Man walking in a brisk wind wears a chaperon that has been caught by a gust. He wears a belt pouch and carries a walking stick, late 14th century.

Older man (chiding an indiscreet young woman, see image below) wears a long, loose houppelande. The fashionable young men wear short tunics, one with dagged edges. The man on the right wears shoes with long pointed toes, late 14th century.

Style gallery

| 1 – Braies | 2 – Shirt and braies |

3 – Servant |

4 – Cotehardie and hood |

5 – Cotehardie |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

6 – Huntsman |

7 – Walking |

8 – Men’s gowns |

1.Braies are worn rolled over a belt at the waist. Catalonia.

2.Shirt is made of rectangles with gussets at shoulder, underarm, and hem.

3.Serving man wears a knee-length tunic with long, tight sleeves over hose. Wears a belt with a waist-pouch or purse. His shoes are pointed. From the Luttrell Psalter, England, c. 1325–35.

4.Bridegroom wears a red cotehardie, hose, and hood, Italy, 1350s.

5.Man in a particolored cotehardie of reddish brown and plaid fabric, 2nd half of the 14th century, Catalonia. The cotehardie fits snugly and is buttoned up the front. A narrow belt is worn around the hips.

6.Huntsman wears side-lacing boots, late 14th century.

7.Man walking in a brisk wind wears a chaperon that has been caught by a gust. He wears a belt pouch and carries a walking stick, late 14th century.

8.Older man (chiding an indiscreet young woman, see image below) wears a long, loose houppelande. The fashionable young men wear short tunics, one with dagged edges. The man on the right wears shoes with long pointed toes, late 14th century.

Working class clothing

Images from a 14th-century manuscript of Tacuinum Sanitatis, a treatise on healthful living, show the clothing of working people: men wear short or knee-length tunics and thick shoes, and women wear knotted kerchiefs and gowns with aprons. For hot summer work, men wear shirts and braies and women wear chemises. Women tuck their gowns up when working.

| Storing olives |

Threshing |

Cheesemaking |

Milking |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Fishing |

Carrying water |

Storing wood |

Harvesting grain |

Source from Wikipedia