BioArt is an art practice where humans work with live tissues, bacteria, living organisms, and life processes. Using scientific processes such as biotechnology (including technologies such as genetic engineering, tissue culture, and cloning) the artworks are produced in laboratories, galleries, or artists’ studios. The scope of BioArt is considered by some artists to be strictly limited to “living forms”, while other artists would include art that uses the imagery of contemporary medicine and biological research, or require that it address a controversy or blind spot posed by the very character of the life sciences.

Bioarte or Bio-Art is one of the most recent trends developed by contemporary art. It has the peculiarity of taking on biotechnology as a means. Cultivation of living tissues, genetics, morphological transformations, biomechanical constructions are some of the techniques used by bio-art artists, posing ethical and social issues to the development in biotechnology.

Although BioArtists work with living matter, there is some debate as to the stages at which matter can be considered to be alive or living. Creating living beings and practicing in the life sciences brings about ethical, social, and aesthetic inquiry. The phrase “BioArt” was coined by Eduardo Kac in 1997 in relation to his artwork Time Capsule. Although it originated at the end of the 20th century through the works of pioneers like Joe Davis Marta de Menezes and artists at SymbioticA, BioArt started to be more widely practiced in the beginning of the 21st century.

This experimentation can involve the artist’s own body (skin cultures, animal blood transfusions), often embodying the traditional fears and hopes associated with these technologies.

There is some debate about the inclusion of works that do not work with techniques on living tissue in the bio-art stream. The works that participate in bio-art should be recognized insofar as they reflect a level of criticism or comment on the existing problematic relationship between society and development in biotechnology.

BioArt is often intended to be shocking or humorous. One survey of the field in Isotope: A Journal of Literary Science and Nature Writing puts it this way: “BioArt is often ludicrous. It can be lumpy, gross, unsanitary, sometimes invisible, and tricky to keep still on the auction block. But at the same time, it does something very traditional that art is supposed to do: draw attention to the beautiful and grotesque details of nature that we might otherwise never see.”

The Bioart has also been developed from the current artistic plastic which involves a manufacturing process in balance with the environment, that is, taking into account the use of recyclable and reusable materials for the production of artistic pieces in balance with the environment. The objective of the Bioart is to offer the public the possibility of developing and contemplating the expression of each artist returning to the roots, to the expression of each culture that is born from the earth and does not harm it. In Venezuela it is developed by different artists, the pioneers being the Bioartesanal Workshop “Un Mundo en Botellas”.

George Gessert is considered by many as an important initiator of the bio-art movement. Eduardo Kac is another of the initiators of the current and his work with living beings. The best known is the Alba rabbit, work in which, through the genetic manipulation of the animal, the color is changed. The SymbioticA is a group founded by Oron Catts and Ionatt Zurr, based at the School of Human Anatomy and Biology at the University of Western Australia. They often use living tissues as sculptural forms, compromising ethical judgments in works, often in a controversial manner. Joe Davis works at MIT and, with the collaboration of scientists, produced several exhibitions.

While raising questions about the role of science in society, “most of these works tend toward social reflection, conveying political and societal criticism through the combination of artistic and scientific processes.”

While most people who practice BioArt are categorized as artists in this new media, they can also be seen as scientists, since the actual medium within a work pertains to molecular structures, and so forth. Because of this dual-acceptance, the Department of Cell Biology at Harvard University invites anyone to submit works based on scientific or artistic value. This can encourage anyone to submit work they strongly respond to.

The laboratory work can pose a challenge to the artist, at first, as the environment is often foreign to the artist. While some artists have prior scientific training, others must be trained to perform the procedures or work in tandem with scientists who can perform the tasks that are required. Bio artists often use formations relating to or engaged with science and scientific practices, such as working with bacteria or live-tissue.

Much of the art involves tissue-culturing and transgenics, a term for a variety of genetic engineering processes through which genetic material from one organism is altered by the addition of synthesized or transplanted genetic material from another organism.

BioArt has been scrutinized for its apparent lack of ethics. USA Today reported that animal rights groups accused Kac and others of using animals unfairly for their own personal gain, and conservative groups question the use of transgenic technologies and tissue-culturing from a moral standpoint.

Alka Chandna, a senior researcher with PETA in Norfolk, Virginia, has stated that using animals for the sake of art is no different from using animal fur for clothing material. “Transgenic manipulation of animals is just a continuum of using animals for human end, regardless of whether it is done to make some sort of sociopolitical critique. The suffering and exacerbation of stress on the animals is very problematic.”

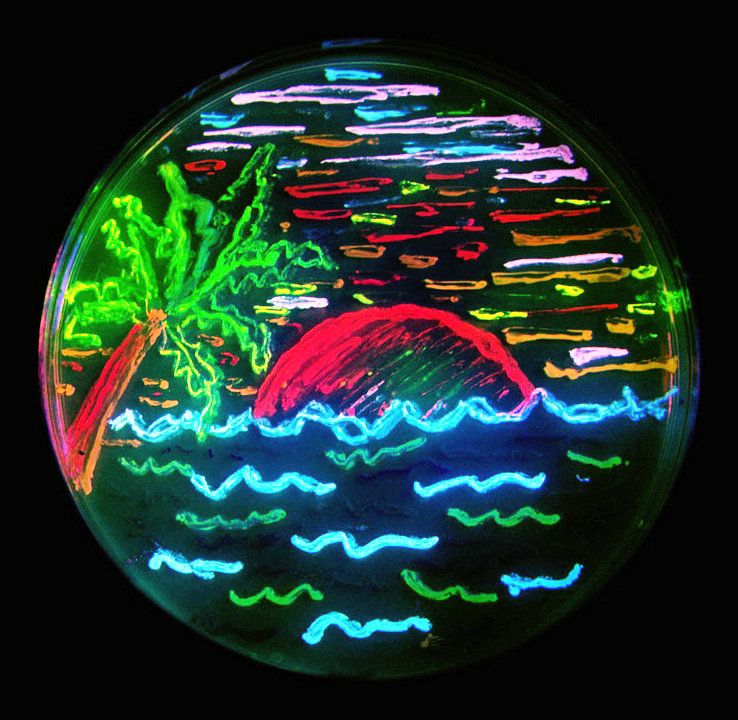

The scope of the term BioArt is a subject of ongoing debate. The primary point of debate centers around whether BioArt must necessarily involve manipulation of biological material, as is the case in microbial art which by definition is made of microbes. A broader definition of the term would include work that addresses the social and ethical considerations of the biological sciences. Under these terms BioArt as a genre has many crossovers with fields such as critical or speculative design. This type of work often reaches a much broader general audience, and is focused on starting discussions in this space, rather than pioneering or even using specific biological practices. Examples in this space include Ray Fish shoes, which advertised shoes made and patterned with genetically engineered stingray skin, and BiteLabs, a biotech startup that attempted to make salami out of meat cultured from celebrity tissue samples. Among the artistic community, however, BioArt is increasingly restricted to disclude work that does not directly involve biological materials.

However, many BioArt projects deal with the manipulation of cells and not whole organisms, such as Victimless Leather by SymbioticA. “An actualized possibility of wearing ‘leather’ without killing an animal is offered as a starting point for cultural discussion. Our intention is not to provide yet another consumer product, but rather to raise questions about our exploitation of other living beings.” These projects were developed precisely to highlight and problematise our relationship to non-human animals and the use of animal products in scientific processes.