Botanical illustration is the art of depicting the form, color, and details of plant species, frequently in watercolor paintings. They must be scientifically accurate but often also have an artistic component and may be printed with a botanical description in book, magazines, and other media or sold as a work of art. Often composed in consultation with a scientific author, their creation requires an understanding of plant morphology and access to specimens and references.

A botanical illustration is an artistic discipline of botany that consists of representing the form, color and details of plant species, often in watercolor on a botanical plate, but sometimes also in pastel or engraving. This botanical representation has a pedagogical and scientific purpose, unlike the art of botany that meets the criteria of beauty and aesthetics, so it is often printed with a botanical description in a book or magazine of botany. The creation of these illustrations requires an understanding of plant morphology and access to samples and references.

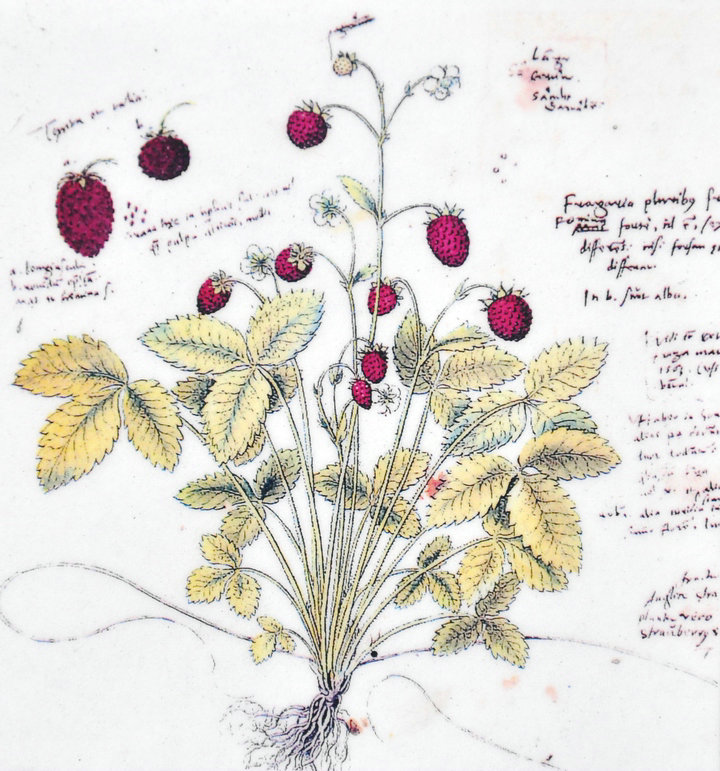

Early herbals and pharmacopoeia of many cultures have included the depiction of plants. This was intended to assist identification of a species, usually with some medicinal purpose. The earliest surviving illustrated botanical work is the Codex vindobonensis. It is a copy of Dioscorides’s De Materia Medica, and was made in the year 512 for Juliana Anicia, daughter of the former Western Roman Emperor Olybrius. The problem of accurately describing plants between regions and languages, before the introduction of taxonomy, were potentially hazardous to medicinal preparations. The low quality of printing of early works sometimes presents difficulties in identifying the species depicted.

When systems of botanical nomenclature began to be published, the need for a drawing or painting became optional. However, it was at this time that the profession of botanical illustrator began to emerge. The eighteenth century saw many advances in the printing processes, and the illustrations became more accurate in colour and detail. The increasing interest of amateur botanists, gardeners, and natural historians provided a market for botanical publications; the illustrations increased the appeal and accessibility of these to the general reader. The field guides, Floras, catalogues and magazines produced since this time have continued to include illustrations. The development of photographic plates has not made illustration obsolete, despite the improvements in reproducing photographs in printed materials. A botanical illustrator is able to create a compromise of accuracy, an idealized image from several specimens, and the inclusion of the face and reverse of the features such as leaves. Additionally, details of sections can be given at a magnified scale and included around the margins around the image.

Recently a renaissance has been occurring in botanical art and illustration. Organizations devoted to furthering the art form are found in the US (American Society of Botanical Artists), UK (Society of Botanical Artists), Australia (Botanical Art Society of Australia), and South Africa (Botanical Artists Association of South Africa), among others. The reasons for this resurgence are many. In addition to the need for clear scientific illustration, botanical depictions continue to be one of the most popular forms of “wall art”. There is an increasing interest in the changes occurring in the natural world, and in the central role plants play in maintaining healthy ecosystems. A sense of urgency has developed in recording today’s changing plant life for future generations. Working in media long understood provides confidence in the long-term conservation of the drawings, paintings, and etchings. Many artists are drawn to more traditional figurative work, and find plant depiction a perfect fit. Working with scientists, conservationists, horticulturists, and galleries locally and around the world, today’s illustrators and artists are pushing the boundaries of what has traditionally been considered part of the genre.

At the end of the 14th century, an illustrated manuscript such as the Erbario Carrarese (British Library, London, Egerton Ms.2020), reveals the increased importance given to the observation of plants. This is an Italian translation (done in Veneto between 1390 and 1404 for Francesco II Carrara da Carrara Herbarium (in Latin), a treatise of medicine originally written in Arabic by Serapion the Younger at the end of 12th century, the book of simple medicines.

Andrea Amadio (born in Venice, died after 1450) was an Italian miniaturist known for having illustrated between 1415 and 1449 the Book of the Simple (known under the name of codex Rinio, according to its second owner, Benedetto Rinio), written by the doctor Niccolò Roccabonella from Conegliano.

The Book of Hours (two volumes), said of the Master-aux-fleurs, on parchment5 has many flowers identifiable in its wide margins. Jean Bourdichon (1456-1521), painter and illuminator of the court of France, represented rather realistically, in the margins of the Great Hours of Anne of Brittany, 337 plants of the garden of the queen, captioned in Latin and in French.

Botany made great progress from the end of the XV century. Artificial seagrasses were printed as early as 1475; in 1485 appeared in Germany De Gart der Gesundheit of Johannes de Cuba, first printed book of natural history. Beginning in 1530, wood engravings based on direct observation of plants began to appear. This is the case of the Otto Brunfels books illustrated by Hans Weiditz: Herbarum vivae eicones (1530-1536, in three parts) and Contrafayt Kräuterbuch (1532-1537, in two parts). 1533 saw the creation of the first chair of botany in Europe, in Padua. In 1544, Luca Ghini (1490-1556), Italian doctor and botanist, founded the Botanical Garden of Pisa (the first university botanical garden in Europe) with the support of Cosimo I de Medici and published his first herbarium, the same year. He is credited with inventing the herbarium (called hortus siccus, dried garden) around 1520 or 1530. His compatriot Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605) as

appeared in the middle of the sixteenth century one of the first flora. Jacopo Ligozzi (1547-1627) worked for Ghini and Aldovrandi.

The Swiss Conrad Gessner (1516-1565) devoted much of his life to botany. He published two works in 1541 and 1542, the rest of his botanical writings waiting for the mid-eighteenth century to be published. The woodcuts that illustrated them were often reused, they represent plants with their roots, flowers and seeds.

The Great Discoveries and the arrival in Europe of unknown plants and other natural wonders gave rise to an enormous interest in nature which led to the accumulation of specimens (in cabinets of curiosities and botanical gardens), then to their classification, to the creation of catalogs, then of botanical works, and thus to the appearance of the scientific illustration. The passion for horticulture created a market for still lifes of flowers (painted for aesthetic purposes), and for miniatures, the more scientific approach.

Leonhart Fuchs (1501-1566) published De Historia Stirpium commentarii insignes (1542), accompanied by illustrations at least as precise as those of Hans Weiditz. The drawings are by Albrecht Meyer and the engravings by Veit Rudolph Speckle. Fuchs includes ornamental plants and plants brought from the Americas, and had the whole plants, including roots, flowers and fruits, shown by nature, to enable their identification. His work has been reissued many times, in several languages. The engravings were also reused. The name and portrait of the illustrators appear in the book.

The Flemish Pieter Van der Borcht the elder (1530-1608) illustrated botanical works from 1565 when the Antwerp printer Christophe Plantin commissioned him boards for the herbarium of Rembert Dodoens. Other commissions (more than 3000 botanical watercolors in all, engraved by Arnold Nicolai, then Gerard van Kampen and Cornelis Muller) followed for the works of Dodoens, Charles de L’Ecluse and Mathias de l’Obel.

The Florum, coronariarum odoratarumque nonnullarum herbarum historia6 of Dodoens (published by Plantin, 1568) offers a description of ornamental flowers with engravings showing whole plants (from flower to root). A chapter is devoted to tulips.

Charles de L’Écluse (1526-1609), a French-speaking Flemish doctor and botanist, created one of the first botanic gardens in Europe, in Leiden, and can be considered the world’s first mycologist and the founder of the horticulture, especially the tulip (which he kept seeds of Ogier Ghiselin Busbecq). He is also the first to provide truly scientific descriptions of plants. He translated the works of Dodoens. Rariorum plantarum historia (published by Plantin in 1601) is an important treatise on botany and mycology illustrated by more than a thousand engravings.

Joris Hoefnagel (1542-1601), a Flemish illuminator, belongs to the transition period between medieval illumination and Renaissance still life painting. He is known for his exact representations of fruits, flowers, animals that were taken as models by many other artists in the following centuries. Also known from Hoefnagel are bird paintings (notably an illustration of the dodo) painted when he worked for the court of Emperor Rudolf II, famous for his cabinet of curiosities. His ‘Amoris Monumentum Matri Charissimae’ (1589) presents a floral arrangement that seems to be perceived at a precise moment, when butterflies, caterpillars and snails appeared. The idea was often repeated. His Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelii (published by his son Jacob, Frankfurt, in 1592) contains 48 engravings due to Jacob (and perhaps Theodore de Bry or his son) from studies that seem made from nature by Joris (who was even supposed to have used a microscope).

Theodore de Bry (1528-98), draftsman and engraver, published in 1612 his Florilegium novum composed of 116 plates representing, as the full title underlines, flowers and plants, with their roots and onions, engraved from nature. It seems that some boards, at least, were borrowed from Pierre Vallet (around 1575-1657), engraver and embroiderer of the kings Henry IV and Louis XIII, who published, him, two florilèges: The garden of the king very Christian Henri IV7 ( 1608) and The Garden of the Very Christian King Loys XIII (1623).

Emanuel Sweerts (1552-1612), a collector of tulips, published another anthology: Florilège by Emanuel Sweerts de Zevenbergen in Amsterdam, where various flowers and other plants are presented, in two parts, drawn from nature and made four languages (Latin, German, French and Dutch). The first part is devoted to 67 bulb plants (32 varieties of tulips), and the second to 43 perennials. Each board (all are borrowed from de Bry’s Florilegium) is numbered and refers to an index where his name appears. The 1612 edition contains a foreword where the author gives the two addresses where tulips can be bought, in Frankfurt and Amsterdam.

Hortus Eystettensis8 (1613) is a “cabinet book” and, more precisely, an anthology: it offers engravings of the plants in the garden that the Prince-Bishop of Eichstätt, Jean Conrad of Gemmingenfit had created by the botanist Basilius Besler . The 367 engravings, mostly from Wolfgang Kilian, could be painted or not.

Crispin de Passe l’Ancien (1564-1637) and especially (or only) his son Crispin II de Passe (around 1597-1670, he worked in Paris) published their Hortus Floridus9 in Utrecht, from 1614 onwards. an engraved anthology of more than 100 rare or rare plants accurately represented and classified according to their flowering season. The first boards represent two views of a Dutch garden.

In 1616 was published Garden of Hyver, or Cabinet of Flowers, containing in XXVI the rarest elegies and signal jewels of the most flowering parterres. Illustrated with excellent figures representing the most beautiful flowers of home gardens (especially anemones and tulips), By Jean Franeau. This work was endowed with an initial index and engravings due to Antoine Serrurier. The flowers most prized by “florists” (garden lovers) are presented in the order of the seasons, starting with spring. (Hortus hyemale / hiemale (winter garden), or hortus siccus (dry garden) was named herbaria, which did not take this name until the eighteenth century.)

In 1631 began the great era of the vellum of the king (see below).

It was at the same time that the idea of the pleasure garden, born in Italy, was taken over in France during the great period of construction of mansions, mainly in Paris, from the beginning of the 17th century. The hotels were often built between a courtyard (street side) and a pleasure garden on which gave the private apartments. The Lambert Hotel, built in 1640, has a terraced garden. Follies such as Folie-Rambouillet (built from 1633 to 1635) were provided with vast “pleasure gardens” to which André Mollet (around 1600-1665) devoted a book: The Garden of Pleasure, containing several gardening designs, 1651. He It treats trees (including fruit trees and orangery plants), the “kitchen garden”, the garden “with flowers” and “ornaments of the garden of pleasure” (general layout, caves, fountains, statues, perspectives). Follow some “drawings” (garden plans, embroidery patterns etc.). The hotel of Évreux was provided with a garden of approval in 1722.

Nicolas Guillaume de La Fleur (1608-1663, according to the website of the British Museum), engraver, painter and draftsman Lorraine, is known to have engraved floral plates in Rome in 1638-39 (published by Frederick de Wit in Amsterdam in 1650- 1706), and having worked in Paris (around 1644) 11.

Balthasar Moncornet (159.-1668), upholsterer, painter, engraver, publisher and prints dealer, arrived in Paris in 1602, installed “1 rue St Jacques at the beautiful cross, opposite St Yves”. His wife Marguerite (born Van der Mael) took over the business after his death, until 1691. He published especially works for ornamentalists, including new book of flowers very useful for the art of goldsmith and other ( Paris, 1645).

The tulipomania continued beyond the collapse of the courts in 1637. Jean Le Clerc (15 ..- 163., Bookseller, publisher and engraver, published his book of flowers where are represented all kinds of tulips, in Paris, in 1650. Charles de La Chesnee-Monstereul followed suit with a book entirely devoted to tulips, Le Floriste franois, dealing with the origin of tulips, the order that must be observed to cultivate and plant them … with a catalog of the names of the tulips published by Eléazar Mangeant (son of the music publisher Jacques Mangeant), in Caen, in 1654. And in 1678, he published at Charles de Sercy (1623-1700? Parisian printer and bookseller) a Treated tulips, with the way to cultivate them well, their names, their colors and their beauty.

The painter Johann Walter (1604-1676) met Johann von Nassau-Idstein (1603-77) when he went to Strasbourg. Returning to his lands in Idstein around 1646, the Count built himself an important cabinet of curiosities, had a garden created, and invited Walter to paint it: The Nassau-Idstein anthology, painted between 1654 and 1672, contains 42 miniatures on vellum of flowers (known or exotic) and fruits, and views of the garden showing fruit-shaped beds.

The approach is much more scientific by Denis Dodart (1634-1707) who directed from 1670 to 1694 the studies of the Royal Academy of Sciences, leading in 1676 to the publication of Memoirs to serve in the history of plants , which proposed to compile a comprehensive (illustrated) catalog of plant species.

We find the same scientific concern in Charles Plumier (1646-1704), botanist and draftsman, who made four trips to America (the first in 1689), brought back a herbarium (lost) and many drawings: Description of the plants of America was published by the second voyage (1693), and Nova plantarum americanarum genera (1703) after the third. These books include planks showing flowers and fruits at different stages of development.

Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656-1708) published in 1694 his first book, Elements of Botany or Method to Know Plants. He states in his warning that “the method followed is based on the structure of flowers and fruits. One can not deviate from it without throwing himself into strange embarrassments. The book is illustrated with 451 excellent boards by Claude Aubriet and immediately obtained a huge success, he translated himself into Latin under the title Institutiones rei herbariae so that it can be read throughout Europe.

At the end of the XVII century appeared the first manuals for amateur painters: Claude Boutet published in 1679 School of the mint: In which one can easily learn to paint without master. A section of the book (chapter 88 and following) is devoted to the painting of flowers. The idea of the textbook was taken up by a former student of Nicolas Robert “Academic receué by Gentlemen of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture”: The Royal Lessons or the way of painting in Mignature Flowers and Oyseaux, by the explanation of the Books of Flowers and Oyseaux of fire Nicolas Robert Fleuriste Composed by Damoiselle Catherine Perrot, Painter Academician, wife of Mme C. Horry Notary Apostolic of the Archbishop of Paris (1686, new edition in 1693) recommend the imitation works by Robert more than those of Baptiste de la Fleur (Preface and Chapter I).

Source From Wikipedia