Forms of Entertainment

Entertainment is any activity that allows human beings to spend their free time to have fun or recreate their mood with a distraction, avoiding boredom and temporarily evading their worries, rejoicing or delighting; for example, playing or reading.

Forms

Banquets

Banquets have been a venue for entertainment since ancient times, continuing until the 21st century, when they are still being used for many of their original purposes – to impress visitors, especially important ones (4, 6, 9); to show hospitality (2, 4, 8); as an occasion to showcase supporting entertainments such as music or dancing, or both (2, 3). They were an integral part of court entertainments (3, 4) and helped entertainers develop their skills (2, 3). They are also important components of celebrations such as coronations (9), weddings (7), birthdays (10) civic or political achievements (5), military engagements or victories (6) as well as religious obligations (1). In modern times, banquets are commercially available, for example, in restaurants (10) and combined with a performance in dinner theatres. Cooking by professional chefs has also become a form of entertainment as part of global competitions such as the Bocuse d’Or.

Music

Music is a supporting component of many kinds of entertainment and most kinds of performance. For example, it is used to enhance storytelling, it is indispensable in dance (1, 4) and opera, and is usually incorporated into dramatic film or theatre productions.

Music is also a universal and popular type of entertainment on its own, constituting an entire performance such as when concerts are given (2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 ). Depending on the rhythm, instrument, performance and style, music is divided into many genres, such as classical, jazz, folk, (4, 5, 8), rock, pop music (6, 9) or traditional (1, 3). Since the 20th century, performed music, once available only to those who could pay for the performers, has been available cheaply to individuals by the entertainment industry, which broadcasts it or pre-records it for sale.

The wide variety of musical performances, whether or not they are artificially amplified (6, 7, 9, 10), all provide entertainment irrespective of whether the performance is from soloists (6), choral (2) or orchestral groups (5, 8), or ensemble (3). Live performances use specialised venues, which might be small or large; indoors or outdoors; free or expensive. The audiences have different expectations of the performers as well as of their own role in the performance. For example, some audiences expect to listen silently and are entertained by the excellence of the music, its rendition or its interpretation (5, 8). Other audiences of live performances are entertained by the ambience and the chance to participate (7, 9). Even more listeners are entertained by pre-recorded music and listen privately (10).

The instruments used in musical entertainment are either solely the human voice (2, 6) or solely instrumental (1, 3) or some combination of the two (4, 5, 7, 8). Whether the performance is given by vocalists or instrumentalists, the performers may be soloists or part of a small or large group, in turn entertaining an audience that might be individual (10), passing by (3), small (1, 2) or large (6, 7, 8, 9). Singing is generally accompanied by instruments although some forms, notably a cappella and overtone singing, are unaccompanied. Modern concerts often use various special effects and other theatrics to accompany performances of singing and dancing (7).

Games

Games are played for entertainment—sometimes purely for entertainment, sometimes for achievement or reward as well. They can be played alone, in teams, or online; by amateurs or by professionals. The players may have an audience of non-players, such as when people are entertained by watching a chess championship. On the other hand, players in a game may constitute their own audience as they take their turn to play. Often, part of the entertainment for children playing a game is deciding who is part of their audience and who is a player.

Equipment varies with the game. Board games, such as Go, Monopoly or backgammon need a board and markers. One of the oldest known board games is Senet, a game played in Ancient Egypt, enjoyed by the pharaoh Tutankhamun. Card games, such as whist, poker and Bridge have long been played as evening entertainment among friends. For these games, all that is needed is a deck of playing cards. Other games, such as bingo, played with numerous strangers, have been organised to involve the participation of non-players via gambling. Many are geared for children, and can be played outdoors, including hopscotch, hide and seek, or Blind man’s bluff. The list of ball games is quite extensive. It includes, for example, croquet, lawn bowling and paintball as well as many sports using various forms of balls. The options cater to a wide range of skill and fitness levels. Physical games can develop agility and competence in motor skills. Number games such as Sudoku and puzzle games like the Rubik’s cube can develop mental prowess.

Video games are played using a controller to create results on a screen. They can also be played online with participants joining in remotely. In the second half of the 20th century and in the 21st century the number of such games increased enormously, providing a wide variety of entertainment to players around the world. Video games are popular in East Asian countries such as South Korea.

Reading

Reading has been a source of entertainment for a very long time, especially when other forms, such as performance entertainments, were (or are) either unavailable or too costly. Even when the primary purpose of the writing is to inform or instruct, reading is well known for its capacity to distract from everyday worries. Both stories and information have been passed on through the tradition of orality and oral traditions survive in the form of performance poetry for example. However, they have drastically declined. “Once literacy had arrived in strength, there was no return to the oral prerogative.” The advent of printing, the reduction in costs of books and an increasing literacy all served to enhance the mass appeal of reading. Furthermore, as fonts were standardised and texts became clearer, “reading ceased being a painful process of decipherment and became an act of pure pleasure”. By the 16th century in Europe, the appeal of reading for entertainment was well established.

Among literature’s many genres are some designed, in whole or in part, purely for entertainment. Limericks, for example, use verse in a strict, predictable rhyme and rhythm to create humour and to amuse an audience of listeners or readers. Interactive books such as “choose your own adventure” can make literary entertainment more participatory.

Comics and cartoons are literary genres that use drawings or graphics, usually in combination with text, to convey an entertaining narrative. Many contemporary comics have elements of fantasy and are produced by companies that are part of the entertainment industry. Others have unique authors who offer a more personal, philosophical view of the world and the problems people face. Comics about superheroes such as Superman are of the first type. Examples of the second sort include the individual work over 50 years of Charles M. Schulz who produced a popular comic called Peanuts about the relationships among a cast of child characters; and Michael Leunig who entertains by producing whimsical cartoons that also incorporate social criticism. The Japanese Manga style differs from the western approach in that it encompasses a wide range of genres and themes for a readership of all ages. Caricature uses a kind of graphic entertainment for purposes ranging from merely putting a smile on the viewer’s face, to raising social awareness, to highlighting the moral characteristics of a person being caricatured.

Comedy

Comedy is both a genre of entertainment and a component of it, providing laughter and amusement, whether the comedy is the sole purpose or used as a form of contrast in an otherwise serious piece. It is a valued contributor to many forms of entertainment, including in literature, theatre, opera, film and games. In royal courts, such as in the Byzantine court, and presumably, also in its wealthy households, “mimes were the focus of orchestrated humour, expected or obliged to make fun of all at court, not even excepting the emperor and members of the imperial family. This highly structured role of jester consisted of verbal humour, including teasing, jests, insult, ridicule, and obscenity and non-verbal humour such as slapstick and horseplay in the presence of an audience.” In medieval times, all comic types – the buffoon, jester, hunchback, dwarf, jokester, were all “considered to be essentially of one comic type: the fool”, who while not necessarily funny, represented “the shortcomings of the individual”.

Shakespeare wrote seventeen comedies that incorporate many techniques still used by performers and writers of comedy—such as jokes, puns, parody, wit, observational humor, or the unexpected effect of irony. One-liner jokes and satire are also used to comedic effect in literature. In farce, the comedy is a primary purpose.

The meaning of the word “comedy” and the audience’s expectations of it have changed over time and vary according to culture. Simple physical comedy such as slapstick is entertaining to a broad range of people of all ages. However, as cultures become more sophisticated, national nuances appear in the style and references so that what is amusing in one culture may be unintelligible in another.

Performance

Live performances before an audience constitute a major form of entertainment, especially before the invention of audio and video recording. Performance takes a wide range of forms, including theatre, music and drama. In the 16th and 17th centuries, European royal courts presented masques that were complex theatrical entertainments involving dancing, singing and acting. Opera is a similarly demanding performance style that remains popular. It also encompass all three forms, demanding a high level of musical and dramatic skill, collaboration and like the masque, production expertise as well.

Audiences generally show their appreciation of an entertaining performance with applause. However, all performers run the risk of failing to hold their audience’s attention and thus, failing to entertain. Audience dissatisfaction is often brutally honest and direct.

“Of course you all ought to know that while singing a good song or, or giving a good recitation… helps to arrest the company’s attention… Such at least was the case with me – the publican devised a plan to bring my entertainment to an end abruptly, and the plan was, he told the waiter to throw a wet towel at me, which, of course, the waiter did… and I received the wet towel, full force, in the face, which staggered me… and had the desired effect of putting an end to me giving any more entertainments in the house.” William McGonagall (Performance artist and poet)

Storytelling

Storytelling is an ancient form of entertainment that has influenced almost all other forms. It is “not only entertainment, it is also thinking through human conflicts and contradictions”. Hence, although stories may be delivered directly to a small listening audience, they are also presented as entertainment and used as a component of any piece that relies on a narrative, such as film, drama, ballet, and opera. Written stories have been enhanced by illustrations, often to a very high artistic standard, for example, on illuminated manuscripts and on ancient scrolls such as Japanese ones. Stories remain a common way of entertaining a group that is on a journey. Showing how stories are used to pass the time and entertain an audience of travellers, Chaucer used pilgrims in his literary work The Canterbury Tales in the 14th century, as did Wu Cheng’en in the 16th century in Journey to the West. Even though journeys can now be completed much faster, stories are still told to passengers en route in cars and aeroplanes either orally or delivered by some form of technology.

The power of stories to entertain is evident in one of the most famous ones—Scheherazade—a story in the Persian professional storytelling tradition, of a woman who saves her own life by telling stories. The connections between the different types of entertainment are shown by the way that stories like this inspire a retelling in another medium, such as music, film or games. For example, composers Rimsky-Korsakov, Ravel and Szymanowski have each been inspired by the Scheherazade story and turned it into an orchestral work; director Pasolini made a film adaptation; and there is an innovative video game based on the tale. Stories may be told wordlessly, in music, dance or puppetry for example, such as in the Javanese tradition of wayang, in which the performance is accompanied by a gamelan orchestra or the similarly traditional Punch and Judy show.

Epic narratives, poems, sagas and allegories from all cultures tell such gripping tales that they have inspired countless other stories in all forms of entertainment. Examples include the Hindu Ramayana and Mahabharata; Homer’s Odyssey and Iliad; the first Arabic novel Hayy ibn Yaqdhan; the Persian epic Shahnameh; the Sagas of Icelanders and the celebrated Tale of the Genji. Collections of stories, such as Grimms’ Fairy Tales or those by Hans Christian Andersen, have been similarly influential. Originally published in the early 19th century, this collection of folk stories significantly influence modern popular culture, which subsequently used its themes, images, symbols, and structural elements to create new entertainment forms.

Some of the most powerful and long-lasting stories are the foundation stories, also called origin or creation myths such as the Dreamtime myths of the Australian aborigines, the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, or the Hawaiian stories of the origin of the world. These too are developed into books, films, music and games in a way that increases their longevity and enhances their entertainment value.

Theatre

Theatre performances, typically dramatic or musical, are presented on a stage for an audience and have a history that goes back to Hellenistic times when “leading musicians and actors” performed widely at “poetical competitions”, for example at “Delphi, Delos, Ephesus”. Aristotle and his teacher Plato both wrote on the theory and purpose of theatre. Aristotle posed questions such as “What is the function of the arts in shaping character? Should a member of the ruling class merely watch performances or be a participant and perform? What kind of entertainment should be provided for those who do not belong to the elite?” The “Ptolemys in Egypt, the Seleucids in Pergamum” also had a strong theatrical tradition and later, wealthy patrons in Rome staged “far more lavish productions”.

Expectations about the performance and their engagement with it have changed over time (1). For example, in England during the 18th century, “the prejudice against actresses had faded” and in Europe generally, going to the theatre, once a socially dubious activity, became “a more respectable middle-class pastime” in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the variety of popular entertainments increased. Operetta and music halls became available, and new drama theatres such as the Moscow Art Theatre and the Suvorin Theatre in Russia opened. At the same time, commercial newspapers “began to carry theatre columns and reviews” that helped make theatre “a legitimate subject of intellectual debate” in general discussions about art and culture. Audiences began to gather to “appreciate creative achievement, to marvel at, and be entertained by, the prominent ‘stars’.” Vaudeville and music halls, popular at this time in the United States, England, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, were themselves eventually superseded.

Plays, musicals, monologues, pantomimes, and performance poetry are part of the very long history of theatre, which is also the venue for the type of performance known as stand-up comedy. In the 20th century, radio and television, often broadcast live, extended the theatrical tradition that continued to exist alongside the new forms.

The stage and the spaces set out in front of it for an audience create a theatre. All types of stage are used with all types of seating for the audience, including the impromptu or improvised (2, 3, 6); the temporary (2); the elaborate (9); or the traditional and permanent (5, 7). They are erected indoors (3, 5, 9) or outdoors (2, 4, 6). The skill of managing, organising and preparing the stage for a performance is known as stagecraft (10). The audience’s experience of the entertainment is affected by their expectations, the stagecraft, the type of stage, and the type and standard of seating provided.

Cinema and film

Films are a major form of entertainment, although not all films have entertainment as their primary purpose: documentary film, for example, aims to create a record or inform, although the two purposes often work together. The medium was a global business from the beginning: “The Lumière brothers were the first to send cameramen throughout the world, instructing them to film everything which could be of interest for the public.” In 1908, Pathé launched and distributed newsreels and by World War I, films were meeting an enormous need for mass entertainment. “In the first decade of the century cinematic programmes combined, at random, fictions and newsfilms.” The Americans first “contrived a way of producing an illusion of motion through successive images,” but “the French were able to transform a scientific principle into a commercially lucrative spectacle”. Film therefore became a part of the entertainment industry from its early days. Increasingly sophisticated techniques have been used in the film medium to delight and entertain audiences. Animation, for example, which involves the display of rapid movement in an art work, is one of these techniques that particularly appeals to younger audiences. The advent of computer-generated imagery (CGI) in the 21st century made it “possible to do spectacle” more cheaply and “on a scale never dreamed of” by Cecil B. DeMille. From the 1930s to 1950s, movies and radio were the “only mass entertainment” but by the second decade of the 21st century, technological changes, economic decisions, risk aversion and globalisation reduced both the quality and range of films being produced. Sophisticated visual effects and CGI techniques, for example, rather than humans, were used not only to create realistic images of people, landscapes and events (both real and fantastic) but also to animate non-living items such as Lego normally used as entertainment as a game in physical form. Creators of The Lego Movie “wanted the audience to believe they were looking at actual Lego bricks on a tabletop that were shot with a real camera, not what we actually did, which was create vast environments with digital bricks inside the computer.” The convergence of computers and film has allowed entertainment to be presented in a new way and the technology has also allowed for those with the personal resources to screen films in a home theatre, recreating in a private venue the quality and experience of a public theatre. This is similar to the way that the nobility in earlier times could stage private musical performances or the use of domestic theatres in large homes to perform private plays in earlier centuries.

Films also re-imagine entertainment from other forms, turning stories, books and plays, for example, into new entertainments. The Story of Film, a documentary about the history of film, gives a survey of global achievements and innovations in the medium, as well as changes in the conception of film-making. It demonstrates that while some films, particularly those in the Hollywood tradition that combines “realism and melodramatic romanticism”, are intended as a form of escapism, others require a deeper engagement or more thoughtful response from their audiences. For example, the award winning Senegalese film Xala takes government corruption as its theme. Charlie Chaplin’s film The Great Dictator was a brave and innovative parody, also on a political theme. Stories that are thousands of years old, such as Noah, have been re-interpreted in film, applying familiar literary devices such as allegory and personification with new techniques such as CGI to explore big themes such as “human folly”, good and evil, courage and despair, love, faith, and death – themes that have been a main-stay of entertainment across all its forms.

As in other media, excellence and achievement in films is recognised through a range of awards, including ones from the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, the Cannes International Film Festival in France and the Asia Pacific Screen Awards.

Dance

The many forms of dance provide entertainment for all age groups and cultures. Dance can be serious in tone, such as when it is used to express a culture’s history or important stories; it may be provocative; or it may put in the service of comedy. Since it combines many forms of entertainment – music, movement, storytelling, theatre – it provides a good example of the various ways that these forms can be combined to create entertainment for different purposes and audiences.

Dance is “a form of cultural representation” that involves not just dancers, but “choreographers, audience members, patrons and impresarios… coming from all over the globe and from vastly varied time periods.” Whether from Africa, Asia or Europe, dance is constantly negotiating the realms of political, social, spiritual and artistic influence.” Even though dance traditions may be limited to one cultural group, they all develop. For example, in Africa, there are “Dahomean dances, Hausa dances, Masai dances and so forth.” Ballet is an example of a highly developed Western form of dance that moved to the theatres from the French court during the time of Louis XIV, the dancers becoming professional theatrical performers. Some dances, such as the quadrille, a square dance that “emerged during the Napoleonic years in France” and other country dances were once popular at social gatherings like balls, but are now rarely performed. On the other hand, many folk dances (such as Scottish Highland dancing and Irish dancing), have evolved into competitions, which by adding to their audiences, has increased their entertainment value. “Irish dance theatre, which sometimes features traditional Irish steps and music, has developed into a major dance form with an international reputation.”

Since dance is often “associated with the female body and women’s experiences”, female dancers, who dance to entertain, have in some cases been regarded as distinct from “decent” women because they “use their bodies to make a living instead of hiding them as much as possible”. Society’s attitudes to female dancers depend on the culture, its history and the entertainment industry itself. For example, while some cultures regard any dancing by women as “the most shameful form of entertainment”, other cultures have established venues such as strip clubs where deliberately erotic or sexually provocative dances such as striptease are performed in public by professional women dancers for mostly male audiences.

Various political regimes have sought to control or ban dancing or specific types of dancing, sometimes because of disapproval of the music or clothes associated with it. Nationalism, authoritarianism and racism have played a part in banning dances or dancing. For example, during the Nazi regime, American dances such as swing, regarded as “completely un-German”, had “become a public offense and needed to be banned”. Similarly, in Shanghai, China, in the 1930s, “dancing and nightclubs had come to symbolise the excess that plagued Chinese society” and officials wondered if “other forms of entertainment such as brothels” should also be banned. Banning had the effect of making “the dance craze” even greater. In Ireland, the Public Dance Hall Act of 1935 “banned – but did not stop – dancing at the crossroads and other popular dance forms such as house and barn dances.” In the US, various dances were once banned, either because like burlesque, they were suggestive, or because, like the Twist, they were associated with African Americans. “African American dancers were typically banned from performing in minstrel shows until after the Civil War.”

Dances can be performed solo (1, 4); in pairs, (2, 3); in groups, (5, 6, 7); or by massed performers (10). They might be improvised (4, 8) or highly choreographed (1, 2, 5, 10); spontaneous for personal entertainment, (such as when children begin dancing for themselves); a private audience, (4); a paying audience (2); a world audience (10); or an audience interested in a particular dance genre (3, 5). They might be a part of a celebration, such as a wedding or New Year (6, 8); or a cultural ritual with a specific purpose, such as a dance by warriors like a haka (7). Some dances, such as traditional dance in 1 and ballet in 2, need a very high level of skill and training; others, such as the can-can, require a very high level of energy and physical fitness. Entertaining the audience is a normal part of dance but its physicality often also produces joy for the dancers themselves (9).

Animals

Animals have been used for the purposes of entertainment for millennia. They have been hunted for entertainment (as opposed to hunted for food); displayed while they hunt for prey; watched when they compete with each other; and watched while they perform a trained routine for human amusement. The Romans, for example, were entertained both by competitions involving wild animals and acts performed by trained animals. They watched as “lions and bears danced to the music of pipes and cymbals; horses were trained to kneel, bow, dance and prance… acrobats turning handsprings over wild lions and vaulting over wild leopards.” There were “violent confrontations with wild beasts” and “performances over time became more brutal and bloodier”.

Circus

A circus, described as “one of the most brazen of entertainment forms”, is a special type of theatrical performance, involving a variety of physical skills such as acrobatics and juggling and sometimes performing animals. Usually thought of as a travelling show performed in a big top, circus was first performed in permanent venues. Philip Astley is regarded as the founder of the modern circus in the second half of the 18th century and Jules Léotard is the French performer credited with developing the art of the trapeze, considered synonymous with circuses. Astley brought together performances that were generally familiar in traditional British fairs “at least since the beginning of the 17th century”: “tumbling, rope-dancing, juggling, animal tricks and so on”. It has been claimed that “there is no direct link between the Roman circus and the circus of modern times…. Between the demise of the Roman ‘circus’ and the foundation of Astley’s Amphitheatre in London some 1300 years later, the nearest thing to a circus ring was the rough circle formed by the curious onlookers who gathered around the itinerant tumbler or juggler on a village green.”

Magic

The form of entertainment known as stage magic or conjuring and recognisable as performance, is based on traditions and texts of magical rites and dogmas that have been a part of most cultural traditions since ancient times. (References to magic, for example, can be found in the Bible, in Hermeticism, in Zoroastrianism, in the Kabbalistic tradition, in mysticism and in the sources of Freemasonry.)

Street performance

Street entertainment, street performance or “busking” are forms of performance that have been meeting the public’s need for entertainment for centuries. It was “an integral aspect of London’s life”, for example, when the city in the early 19th century was “filled with spectacle and diversion”. Minstrels or troubadours are part of the tradition. The art and practice of busking is still celebrated at annual busking festivals.

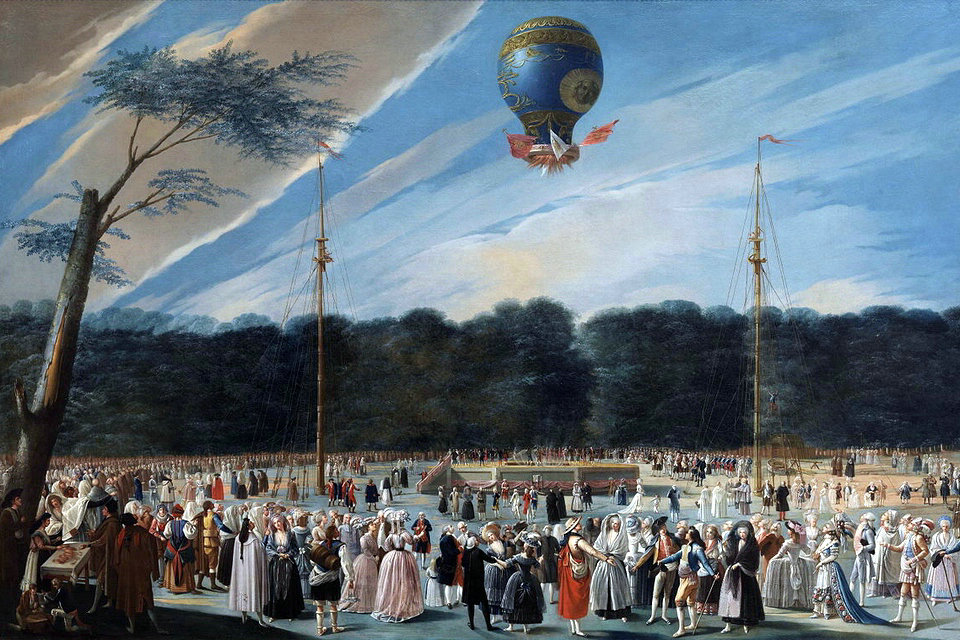

Parades

Parades are held for a range of purposes, often more than one. Whether their mood is sombre or festive, being public events that are designed to attract attention and activities that necessarily divert normal traffic, parades have a clear entertainment value to their audiences. Cavalcades and the modern variant, the motorcade, are examples of public processions. Some people watching the parade or procession may have made a special effort to attend, while others become part of the audience by happenstance. Whatever their mood or primary purpose, parades attract and entertain people who watch them pass by. Occasionally, a parade takes place in an improvised theatre space (such as the Trooping the Colour in 8) and tickets are sold to the physical audience while the global audience participates via broadcast.

Fireworks

Fireworks are a part of many public entertainments and have retained an enduring popularity since they became a “crowning feature of elaborate celebrations” in the 17th century. First used in China, classical antiquity and Europe for military purposes, fireworks were most popular in the 18th century and high prices were paid for pyrotechnists, especially the skilled Italian ones, who were summoned to other countries to organise displays. Fire and water were important aspects of court spectacles because the displays “inspired by means of fire, sudden noise, smoke and general magnificence the sentiments thought fitting for the subject to entertain of his sovereign: awe fear and a vicarious sense of glory in his might. Birthdays, name-days, weddings and anniversaries provided the occasion for celebration.” One of the most famous courtly uses of fireworks was one used to celebrate the end of the War of the Austrian Succession and while the fireworks themselves caused a fire, the accompanying Music for the Royal Fireworks written by Handel has been popular ever since. Aside from their contribution to entertainments related to military successes, courtly displays and personal celebrations, fireworks are also used as part of religious ceremony. For example, during the Indian Dashavatara Kala of Gomantaka “the temple deity is taken around in a procession with a lot of singing, dancing and display of fireworks”.

Sport

Sporting competitions have always provided entertainment for crowds. To distinguish the players from the audience, the latter are often known as spectators. Developments in stadium and auditorium design, as well as in recording and broadcast technology, have allowed off-site spectators to watch sport, with the result that the size of the audience has grown ever larger and spectator sport has become increasingly popular. Two of the most popular sports with global appeal are association football and cricket. Their ultimate international competitions, the World Cup and test cricket, are broadcast around the world. Beyond the very large numbers involved in playing these sports, they are notable for being a major source of entertainment for many millions of non-players worldwide. A comparable multi-stage, long-form sport with global appeal is the Tour de France, unusual in that it takes place outside of special stadia, being run instead in the countryside.

Aside from sports that have world-wide appeal and competitions, such as the Olympic Games, the entertainment value of a sport depends on the culture and country where people play it. For example, in the United States, baseball and basketball games are popular forms of entertainment; in Bhutan, the national sport is archery; in New Zealand, it is rugby union; in Iran, it is freestyle wrestling. Japan’s unique sumo wrestling contains ritual elements that derive from its long history. In some cases, such as the international running group Hash House Harriers, participants create a blend of sport and entertainment for themselves, largely independent of spectator involvement, where the social component is more important than the competitive.

Fairs, expositions, shopping

Fairs and exhibitions have existed since ancient and medieval times, displaying wealth, innovations and objects for trade and offering specific entertainments as well as being places of entertainment in themselves. Whether in a medieval market or a small shop, “shopping always offered forms of exhilaration that took one away from the everyday”. However, in the modern world, “merchandising has become entertainment: spinning signs, flashing signs, thumping music… video screens, interactive computer kiosks, day care.. cafés”.

Source from Wikipedia