Hybrid vehicle

A hybrid vehicle uses two or more distinct types of power, such as internal combustion engine to drive an electric generator that powers an electric motor, e.g. in diesel-electric trains using diesel engines to drive an electric generator that powers an electric motor, and submarines that use diesels when surfaced and batteries when submerged. Other means to store energy include pressurized fluid in hydraulic hybrids.

The basic principle with hybrid vehicles is that the different motors work better at different speeds; the electric motor is more efficient at producing torque, or turning power, and the combustion engine is better for maintaining high speed (better than typical electric motor). Switching from one to the other at the proper time while speeding up yields a win-win in terms of energy efficiency, as such that translates into greater fuel efficiency, for example.

How hybrid-electric vehicles work

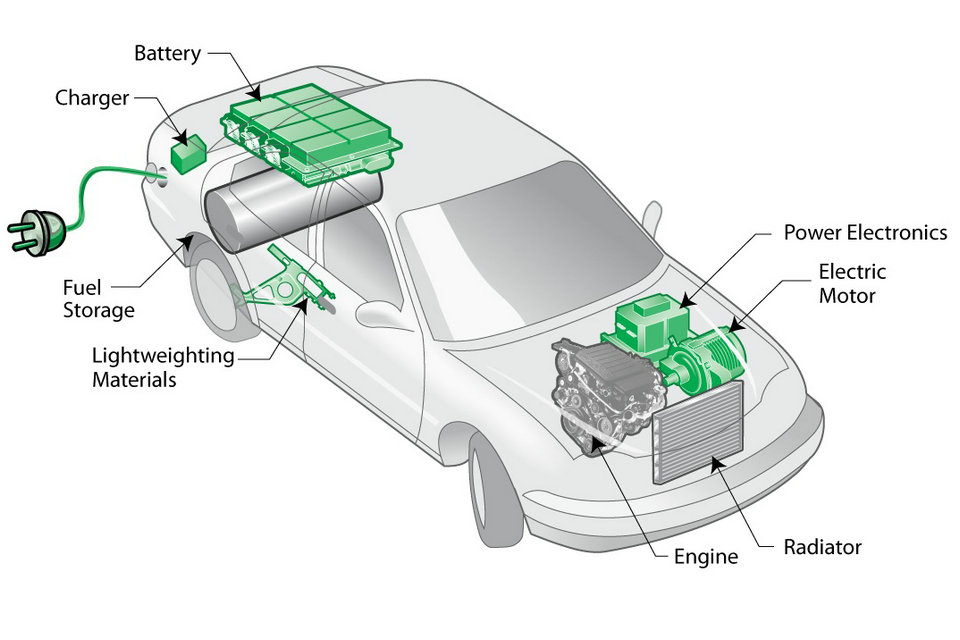

Hybrids-Electric vehicles (HEVs) combine the advantage of gasoline engines and electric motors. The key areas for efficiency or performance gains are regenerative braking, dual power sources, and less idling.

Regenerate Braking.The drivetrain can be used to convert kinetic energy (from the moving car) into stored electrical energy (batteries). The same electric motor that powers the drivetrain is used to resist the motion of the drivetrain. This applied resistance from the electric motor causes the wheel to slow down and simultaneously recharge the batteries.

Dual Power. Power can come from either the engine, motor or both depending on driving circumstances. Additional power to assist the engine in accelerating or climbing might be provided by the electric motor. Or more commonly, a smaller electric motor provides all of the power for low-speed driving conditions and is augmented by the engine at higher speeds.

Automatic Start/Shutoff. It automatically shuts off the engine when the vehicle comes to a stop and restarts it when the accelerator is pressed down. This automation is much simpler with an electric motor. Also see dual power above.

Summary operating principle

Hybrid vehicles combine several energy sources, often one of which is thermal and the other electric. The very simplified overall principle of this type of engine is to take advantage of the advantages of each type of engine while minimizing their disadvantages.

Four hybridization architectures are possible:

in series: the engine drives an alternator, the latter provides electricity to an electric motor, also recharging a buffer battery without directly providing torque to the axle like diesel-electric locomotives

in parallel: the heat engine and the electric motor supply their power to the axle via a conventional transmission, via separate couplings.

power bypass: the engine provides power to the axle and also drives a generator recharging a battery that powers an electric motor.

extended range: a conventional electric vehicle increases are autonomy through a heat engine driving an electric generator to recharge the batteries.

Peugeot uses an original parallel type solution where the front axle is driven by a heat engine with conventional transmission while the rear axle is driven by electric motors. This allows different configurations including an “all electric” for a few kilometers and another “all terrain”.

The small hybrid vehicles are characterized by a good energy efficiency and regularly allow consumption to 100 km urban less than 5 liters (for an onboard electrical power of the order of 50 kW in an average vehicle, Toyota Prius type). Large hybrid vehicles, on the other hand, use hybridization to increase power.

Power

Power sources for hybrid vehicles include:

Coal, wood or other solid combustibles

Compressed or liquefied natural gas

Petrol (gasoline) or Diesel fuel

Human powered e.g. pedaling or rowing

Electromagnetic fields, Radio waves

Electric batteries/capacitors

Overhead electricity

Hydraulic accumulator

Hydrogen

Flywheel

Solar

Wind

Vehicle type

Two-wheeled and cycle-type vehicles

Mopeds, electric bicycles, and even electric kick scooters are a simple form of a hybrid, powered by an internal combustion engine or electric motor and the rider’s muscles. Early prototype motorcycles in the late 19th century used the same principle.

In a parallel hybrid bicycle human and motor torques are mechanically coupled at the pedal or one of the wheels, e.g. using a hub motor, a roller pressing onto a tire, or a connection to a wheel using a transmission element. Most motorized bicycles, mopeds are of this type.

In a series hybrid bicycle (SHB) (a kind of chainless bicycle) the user pedals a generator, charging a battery or feeding the motor, which delivers all of the torque required. They are commercially available, being simple in theory and manufacturing.

The first published prototype of an SHB is by Augustus Kinzel (US Patent 3’884’317) in 1975. In 1994 Bernie Macdonalds conceived the Electrilite SHB with power electronics allowing regenerative braking and pedaling while stationary. In 1995 Thomas Muller designed and built a “Fahrrad mit elektromagnetischem Antrieb” for his 1995 diploma thesis. In 1996 Jürg Blatter and Andreas Fuchs of Berne University of Applied Sciences built an SHB and in 1998 modified a Leitra tricycle (European patent EP 1165188). Until 2005 they built several prototype SH tricycles and quadricycles. In 1999 Harald Kutzke described an “active bicycle”: the aim is to approach the ideal bicycle weighing nothing and having no drag by electronic compensation.

A series hybrid electric-petroleum bicycle (SHEPB) is powered by pedals, batteries, a petrol generator, or plug-in charger – providing flexibility and range enhancements over electric-only bicycles.

A SHEPB prototype made by David Kitson in Australia in 2014 used a lightweight brushless DC electric motor from an aerial drone and small hand-tool sized internal combustion engine, and a 3D printed drive system and lightweight housing, altogether weighing less than 4.5 kg. Active cooling keeps plastic parts from softening. The prototype uses a regular electric bicycle charge port.

Heavy vehicle

Hybrid power trains use diesel-electric or turbo-electric to power railway locomotives, buses, heavy goods vehicles, mobile hydraulic machinery, and ships. A diesel/turbine engine drives an electric generator or hydraulic pump, which powers electric/hydraulic motor(s) – strictly an electric/hydraulic transmission (not a hybrid), unless it can accept power from outside. With large vehicles conversion losses decrease, and the advantages in distributing power through wires or pipes rather than mechanical elements become more prominent, especially when powering multiple drives — e.g. driven wheels or propellers. Until recently most heavy vehicles had little secondary energy storage, e.g. batteries/hydraulic accumulators — excepting non-nuclear submarines, one of the oldest production hybrids, running on diesels while surfaced and batteries when submerged. Both series and parallel setups were used in WW2 submarines.

Rail transport

A hybrid train is a locomotive, railcar or train that uses an onboard rechargeable energy storage system (RESS), placed between the power source (often a diesel engine prime mover) and the traction transmission system connected to the wheels. Since most diesel locomotives are diesel-electric, they have all the components of a series hybrid transmission except the storage battery, making this a relatively simple prospect.

Cranes

Railpower Technologies engineers working with TSI Terminal Systems are testing a hybrid diesel electric power unit with battery storage for use in Rubber Tyred Gantry (RTG) cranes. RTG cranes are typically used for loading and unloading shipping containers onto trains or trucks in ports and container storage yards. The energy used to lift the containers can be partially regained when they are lowered. Diesel fuel and emission reductions of 50–70% are predicted by Railpower engineers. First systems are expected to be operational in 2007.

Road transport, commercial vehicles

Hybrid systems are coming into use for trucks, buses and other heavy highway vehicles. Small fleet sizes and installation costs are compensated by fuel savings,.[needs update] With advances such as higher capacity, lowered battery cost etc. Toyota, Ford, GM and others are introducing hybrid pickups and SUVs. Kenworth Truck Company recently introduced the Kenworth T270 Class 6 that for city usage seems to be competitive. FedEx and others are investing in hybrid delivery vehicles — particularly for city use where hybrid technology may pay off first. As of December 2013 FedEx is trialling two delivery trucks with Wrightspeed electric motors and diesel generators; the retrofit kits are claimed to pay for themselves in a few years. The diesel engines run at a constant RPM for peak efficiency.

Military off-road vehicles

Since 1985, the US military has been testing serial hybrid Humvees and have found them to deliver faster acceleration, a stealth mode with low thermal signature/ near silent operation, and greater fuel economy.

Ships

Ships with both mast-mounted sails and steam engines were an early form of hybrid vehicle. Another example is the diesel-electric submarine. This runs on batteries when submerged and the batteries can be re-charged by the diesel engine when the craft is on the surface.

Newer hybrid ship-propulsion schemes include large towing kites manufactured by companies such as SkySails. Towing kites can fly at heights several times higher than the tallest ship masts, capturing stronger and steadier winds.

Aircraft

The Boeing Fuel Cell Demonstrator Airplane has a Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) fuel cell/lithium-ion battery hybrid system to power an electric motor, which is coupled to a conventional propeller. The fuel cell provides all power for the cruise phase of flight. During takeoff and climb, the flight segment that requires the most power, the system draws on lightweight lithium-ion batteries.

The demonstrator aircraft is a Dimona motor glider, built by Diamond Aircraft Industries of Austria, which also carried out structural modifications to the aircraft. With a wing span of 16.3 meters (53 feet), the airplane will be able to cruise at about 100 km/h (62 mph) on power from the fuel cell.

Hybrid FanWings have been designed. A FanWing is created by two engines with the capability to autorotate and landing like a helicopter.

Engine type

Hybrid electric-petroleum vehicles

When the term hybrid vehicle is used, it most often refers to a Hybrid electric vehicle. These encompass such vehicles as the Saturn Vue, Toyota Prius, Toyota Yaris, Toyota Camry Hybrid, Ford Escape Hybrid, Toyota Highlander Hybrid, Honda Insight, Honda Civic Hybrid, Lexus RX 400h and 450h, Hyundai Ioniq and others. A petroleum-electric hybrid most commonly uses internal combustion engines (using a variety of fuels, generally gasoline or Diesel engines) and electric motors to power the vehicle. The energy is stored in the fuel of the internal combustion engine and an electric battery set. There are many types of petroleum-electric hybrid drivetrains, from Full hybrid to Mild hybrid, which offer varying advantages and disadvantages.

William H. Patton filed a patent application for a gasoline-electric hybrid rail-car propulsion system in early 1889, and for a similar hybrid boat propulsion system in mid 1889. There is no evidence that his hybrid boat met with any success, but he built a prototype hybrid tram and sold a small hybrid locomotive.

In 1899, Henri Pieper developed the world’s first petro-electric hybrid automobile. In 1900, Ferdinand Porsche developed a series-hybrid using two motor-in-wheel-hub arrangements with an internal combustion generator set providing the electric power; Porsche’s hybrid set two speed records. While liquid fuel/electric hybrids date back to the late 19th century, the braking regenerative hybrid was invented by David Arthurs, an electrical engineer from Springdale, Arkansas in 1978–79. His home-converted Opel GT was reported to return as much as 75 mpg with plans still sold to this original design, and the “Mother Earth News” modified version on their website.

The plug-in-electric-vehicle (PEV) is becoming more and more common. It has the range needed in locations where there are wide gaps with no services. The batteries can be plugged into house (mains) electricity for charging, as well being charged while the engine is running.

Continuously outboard recharged electric vehicle (COREV)

Some battery electric vehicles (BEVs) can be recharged while the user drives. Such a vehicle establishes contact with an electrified rail, plate or overhead wires on the highway via an attached conducting wheel or other similar mechanism (see Conduit current collection). The BEV’s batteries are recharged by this process—on the highway—and can then be used normally on other roads until the battery is discharged. For example, some of the battery-electric locomotives used for maintenance trains on the London Underground are capable of this mode of operation.

Developing a BEV infrastructure would provide the advantage of virtually unrestricted highway range. Since many destinations are within 100 km of a major highway, BEV technology could reduce the need for expensive battery systems. Unfortunately, private use of the existing electrical system is almost universally prohibited. Besides, the technology for such electrical infrastructure is largely outdated and, outside some cities, not widely distributed (see Conduit current collection, trams, electric rail, trolleys, third rail). Updating the required electrical and infrastructure costs could perhaps be funded by toll revenue or by dedicated transportation taxes.

Hybrid fuel (dual mode)

In addition to vehicles that use two or more different devices for propulsion, some also consider vehicles that use distinct energy sources or input types (“fuels”) using the same engine to be hybrids, although to avoid confusion with hybrids as described above and to use correctly the terms, these are perhaps more correctly described as dual mode vehicles:

Some electric trolleybuses can switch between an on-board diesel engine and overhead electrical power depending on conditions (see dual mode bus). In principle, this could be combined with a battery subsystem to create a true plug-in hybrid trolleybus, although as of 2006, no such design seems to have been announced.

Flexible-fuel vehicles can use a mixture of input fuels mixed in one tank — typically gasoline and ethanol, methanol, or biobutanol.

Bi-fuel vehicle: Liquified petroleum gas and natural gas are very different from petroleum or diesel and cannot be used in the same tanks, so it would be impossible to build an (LPG or NG) flexible fuel system. Instead vehicles are built with two, parallel, fuel systems feeding one engine. For example, some Chevrolet Silverado 2500 HDs can effortlessly switch between petroleum and natural gas, offering a range of over 1000 km (650 miles). While the duplicated tanks cost space in some applications, the increased range, decreased cost of fuel, and flexibility where LPG or CNG infrastructure is incomplete may be a significant incentive to purchase. While the US Natural gas infrastructure is partially incomplete, it is increasing at a fast pace, and already has 2600 CNG stations in place. With a growing fueling station infrastructure, a large scale adoption of these bi-fuel vehicles could be seen in the near future. Rising gas prices may also push consumers to purchase these vehicles. When gas prices trade around $4.00, the price per MMBTU of gasoline is $28.00, compared to natural gas’s $4.00 per MMBTU. On a per unit of energy comparative basis, this makes natural gas much cheaper than gasoline. All of these factors are making CNG-Gasoline bi-fuel vehicles very attractive.

Some vehicles have been modified to use another fuel source if it is available, such as cars modified to run on autogas (LPG) and diesels modified to run on waste vegetable oil that has not been processed into biodiesel.

Power-assist mechanisms for bicycles and other human-powered vehicles are also included (see Motorized bicycle).

Fluid power hybrid

Hydraulic hybrid and pneumatic hybrid vehicles use an engine to charge a pressure accumulator to drive the wheels via hydraulic (liquid) or pneumatic (compressed air) drive units. In most cases the engine is detached from the drivetrain, serving solely to charge the energy accumulator. The transmission is seamless. Regenerative braking can be used to recover some of the supplied drive energy back into the accumulator.

Petro-air hybrid

A French company, MDI, has designed and has running models of a petro-air hybrid engine car. The system does not use air motors to drive the vehicle, being directly driven by a hybrid engine. The engine uses a mixture of compressed air and gasoline injected into the cylinders. A key aspect of the hybrid engine is the “active chamber”, which is a compartment heating air via fuel doubling the energy output. Tata Motors of India assessed the design phase towards full production for the Indian market and moved into “completing detailed development of the compressed air engine into specific vehicle and stationary applications”.

Petro-hydraulic hybrid

Petro-hydraulic configurations have been common in trains and heavy vehicles for decades. The auto industry recently focused on this hybrid configuration as it now shows promise for introduction into smaller vehicles.

In petro-hydraulic hybrids, the energy recovery rate is high and therefore the system is more efficient than electric battery charged hybrids using the current electric battery technology, demonstrating a 60% to 70% increase in energy economy in US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) testing. The charging engine needs only to be sized for average usage with acceleration bursts using the stored energy in the hydraulic accumulator, which is charged when in low energy demanding vehicle operation. The charging engine runs at optimum speed and load for efficiency and longevity. Under tests undertaken by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), a hydraulic hybrid Ford Expedition returned 32 miles per US gallon (7.4 L/100 km; 38 mpg‑imp) City, and 22 miles per US gallon (11 L/100 km; 26 mpg‑imp) highway. UPS currently has two trucks in service using this technology.

The petro-hydraulic hybrid system has faster and more efficient charge/discharge cycling than petro-electric hybrids and is also cheaper to build. The accumulator vessel size dictates total energy storage capacity and may require more space than an electric battery set. Any vehicle space consumed by a larger size of accumulator vessel may be offset by the need for a smaller sized charging engine, in HP and physical size.

Research is underway in large corporations and small companies. Focus has now switched to smaller vehicles. The system components were expensive which precluded installation in smaller trucks and cars. A drawback was that the power driving motors were not efficient enough at part load. A British company (Artemis Intelligent Power) made a breakthrough introducing an electronically controlled hydraulic motor/pump, the Digital Displacement® motor/pump. The pump is highly efficient at all speed ranges and loads, giving feasibility to small applications of petro-hydraulic hybrids. The company converted a BMW car as a test bed to prove viability. The BMW 530i, gave double the mpg in city driving compared to the standard car. This test was using the standard 3,000 cc engine, with a smaller engine the figures would have been more impressive. The design of petro-hydraulic hybrids using well sized accumulators allows downsizing an engine to average power usage, not peak power usage. Peak power is provided by the energy stored in the accumulator. A smaller more efficient constant speed engine reduces weight and liberates space for a larger accumulator.

Current vehicle bodies are designed around the mechanicals of existing engine/transmission setups. It is restrictive and far from ideal to install petro-hydraulic mechanicals into existing bodies not designed for hydraulic setups. One research project’s goal is to create a blank paper design new car, to maximize the packaging of petro-hydraulic hybrid components in the vehicle. All bulky hydraulic components are integrated into the chassis of the car. One design has claimed to return 130 mpg in tests by using a large hydraulic accumulator which is also the structural chassis of the car. The small hydraulic driving motors are incorporated within the wheel hubs driving the wheels and reversing to claw-back kinetic braking energy. The hub motors eliminates the need for friction brakes, mechanical transmissions, drive shafts and U joints, reducing costs and weight. Hydrostatic drive with no friction brakes are used in industrial vehicles. The aim is 170 mpg in average driving conditions. Energy created by shock absorbers and kinetic braking energy that normally would be wasted assists in charging the accumulator. A small fossil fuelled piston engine sized for average power use charges the accumulator. The accumulator is sized at running the car for 15 minutes when fully charged. The aim is a fully charged accumulator which will produce a 0-60 mph acceleration speed of under 5 seconds using four wheel drive.

Electric-human power hybrid vehicle

Another form of hybrid vehicle are human power-electric vehicles. These include such vehicles as the Sinclair C5, Twike, electric bicycles, and electric skateboards.

Hybrid vehicle power train configurations

Parallel hybrid

In a parallel hybrid vehicle an electric motor and an internal combustion engine are coupled such that they can power the vehicle either individually or together. Most commonly the internal combustion engine, the electric motor and gear box are coupled by automatically controlled clutches. For electric driving the clutch between the internal combustion engine is open while the clutch to the gear box is engaged. While in combustion mode the engine and motor run at the same speed.

The first mass production parallel hybrid sold outside Japan was the 1st generation Honda Insight.

Mild parallel hybrid

These types use a generally compact electric motor (usually