A jali or jaali, (Urdu: جالی Hindi:जाली jālī, meaning “net”) is the term for a perforated stone or latticed screen, usually with an ornamental pattern constructed through the use of calligraphy and geometry. This form of architectural decoration is common in Hindu temple architecture, Indo-Islamic Architecture and more generally in Islamic Architecture.

Early jali work was built by carving into stone, generally in geometric patterns, while later the Mughals used very finely carved plant-based designs, as at the Taj Mahal. They also often added pietra dura inlay to the surrounds, using marble and semi-precious stones.

The jali helps in lowering the temperature by compressing the air through the holes. Also when the air passes through these openings, its velocity increases giving profound diffusion. It has been observed that humid areas like Kerala and Konkan have larger holes with overall lower opacity than compared with the dry climate regions of Gujarat and Rajasthan.

With compactness of the residential areas in the modern India, jalis became less frequent for privacy and security matters.

Development and function

Indian temples

The lattice windows in India are connected with the development of the brick Hindu Temple of Freibay, which consists of a square cella ( garbhagriha ) in the core and in its basic form. This windowless, dark altar room contains the statue of the gods or a lingam . In his need for seclusion, he goes back to earlier cave temples. The Sanskrit words garbha and griha mean “womb” (also “world cave”) or “house” – Indian temples are a figurative art.

In seclusion, monks communities of the Jains , Buddhists and Ajivikas created cave temples ( chaityas ) and cave dwellings ( viharas ). From the 2nd century BC Chr., Such early cave monasteries are preserved. The monks probably transferred constructive elements of an earlier wooden architecture (beams) and design details from the timber construction such as balcony railings and lattice windows in a timeless “petrified” form.

The Gupta- temporal temple 17 in Sanchi (central India) with a short portico ( mandapa ) dates from the 4th / early 5th century and is considered to be the oldest surviving free temple in India (see also Gupta Temple ). In the 5th century BC (pre- Chalukya period), an extension of the ground floor led to a group of temples in South India’s Aihole at Lad Khan, a room with a Nandi in the center, now surrounded by a double row of columns , The heavy and rock-like structure is windowless at the western back, since the cult icon for Shiva , has on the entrance side in the east a pillared porch and on the other two sides each three window openings with the oldest, carefully crafted window bars on Indian temples , According to these geometric patterns, the jalis can be imagined at the late 6th century, but partly poorly preserved temples whose cella in the further development of a transformation path ( pradakshinapatha ) is surrounded.

One of the earliest surviving temples of the Gupta period is the Mahadeva Temple, built in the second half of the 5th century, in the northern Indian city of Nachna (Panna district, Madhya Pradesh ). The temple, which is built of coarse stone blocks and has a Shikhara tower construction, has windows on three sides with relief soffits arranged in three stripes. The window opening is divided vertically by two stone columns and behind them filled with jalis, which form a simple right-angled braiding pattern. From the outer frame to the Jali lattice this results in a multiple depth graduation. Also built about the same time and offset opposite Parvati Temple has two early Jali windows that are fitted into the outer walls of the Cella.

In the middle of the 7th century and at the beginning of the 8th century, Jali windows are used in South Indian temples. In particular, the builders of the Badami- based Chalukyas adopted the forms developed in northern India, converted them only slightly and used them for their temples: these include the Kumara Brahma Temple and the Vira Brahma Temple in Alampur , the Sivanandisvara Temple in Kadamarakalava and the Sangamesvara Temple in Kudaveli . Around this time, Jalis appeared as a play of light and shadow on the outer walls of the Cella and also on the lobbies ( mandapas ) of the early Chalukya temples of Aihole, Pattadakal and Mahakuta .

In front of Cave 15, the second-quarter 8th century Dasavatara Cave in Ellora, there is a megalithic pavilion with large-scale geometrical jali patterns. On the hill above Shravanabelagola , from the 8th century, a series of small Jain temples ( Basti, Basadi ) with Dravidian roof construction were erected. The Chandragupta Basti contains two jalis with sculptural reliefs depicting scenes from the life of Jain saint Acharya Bhadrabahu (433- c. 357 bc) and the Maurya chanter Chandragupta Maurya .

Jalis at Indian temples not only fulfill a decorative task and provide a certain amount of light that does not interfere with the mystical experience of darkness, but also to separate the inner sacral sphere of the temple from the outer world. Walking through the portals of the vestibule and the cella, the believer walks past lateral guardian figures who symbolically perform the same screening function. With the spread of Indian culture to Southeast Asia, the architecture of the Indian temples was basically preserved and developed regionally. The Khmer temples, which are predominantly located in present-day Cambodia , and the Cham temples in Vietnam usually carried the Jalis’ function in the window frames, turned stone pillars. In contrast, Jalis at Mandapas and the outer passages of the numerous Burmese temples of Bagan experienced a typical national design. The thick brick walls of the Bagan temple date from the 11th to the beginning of the 13th century. The dark passages around the Cella, with its corbelled vault and niches for Buddha figures, are given some light, as in the case of the Abeyadana – and at the Nagayon temple by stone jalis.

Jalis of stone on Islamic cult buildings and palaces

Between the medieval Hindu temples and the buildings of the Islamic rulers there were architectural takeovers in the construction and ornamentation on both sides. Of the secular buildings of Indo-Islamic architecture at this time is little preserved. The 1450 built Badal Mahal Gate in Chanderi in the former Sultanate Malwa is a very unusual for Islamic arches Jalis use. At the top of the two arches hangs a four-part Jali in the form of a hinged window and fills the entire arch surface.

This Jali can be seen as a precursor to the built around 1591/92 Charminar in Hyderabad seen in his function to fill a space decorative. The gate building with four keel bows in the center of intersecting street axes receives its dominating appearance through minarets at the corners, which tower far beyond the building intended for passage. To visually reduce the height of the slender towers, they were articulated by cantilevered, covered balconies ( jaroka ). On the other hand, the central structure was raised by two levels of a window wall, which fill a space between the towers and at the same time make them transparent through the inserted jalis. At the Charminar for the first time parapet walls on the roof, which were previously completed with pinnacles , designed by Jalis. The following buildings in Hyderabad have battlements and preferably jalis, often in combination. The mausoleums of the 16th century Qutub Shahi dynasty are domed central buildings. Some of them have battlemented balcony balustrades with jali fields crowned by pinnacles, as well as Mecca Masjid (Mecca Mosque), completed in the 17th century in Hyderabad.

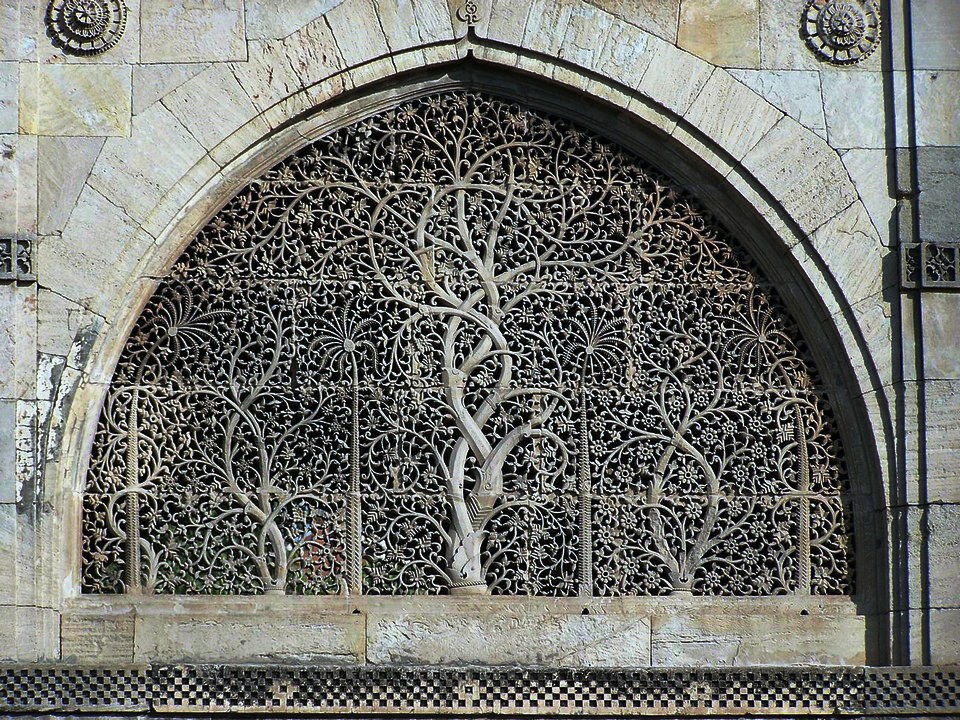

A highlight in the design of Jalis shortly before or at the beginning of the Mughal Empire is the Sidi Saiyad Mosque in Ahmedabad , which was completed in 1515 or 1572 . Named after its builder Sheikh Sayid Sultani, the small courtyard mosque is surrounded on three sides by sandstone walls, whose pointed-arch windows are closed by elaborate marble jalis. Flowers and the branches of a tree entwine in the filigree Jali latticework.

In the former capital of the Mughal empire, Fatehpur Sikri , the single-storey mausoleum of Salim Chishti in the courtyard of the Jama Masjid, made entirely of white marble, stands out beneath the red-brown sandstone palaces. The 15-meter-long pavilion-like square building was built between 1571 and 1580 in honor of Sufi saint Sheikh Salim. Protected on all four sides and by a protruding roof projection, the walls consist almost entirely of floor-to-ceiling Jali grids, whose finest network structure is dissolved in the interior of the daylight into tiny white dots.

The Akbar mausoleum in Sikandra , a suburb of Agra , was begun around 1600 and completed inscribed in 1612-1614. In the mausoleum of red sandstone and the broad, multi-level gate, large arched windows are divided into individual fields with geometric jali lattices of marble.

Completed in 1626, the Itmad-ud-Daulah Mausoleum on the left bank of the Yamuna in Agra is a one-storey square building with a small paved pavilion with a flat dome ( Baradari ). Itimad-ud-Daula (Mirza Ghiyas Beg) was the father of Jahangir’s wife Nur Jahan . Although the early Mughal buildings were still predominantly made of reddish sandstone, this tomb is made of white marble with inlaid polychrome mosaic stones ( pietra dura ). It forms the transition to the refined, more Persian influenced Mughal style in the 17th century, culminating in the Taj Mahal . The light enters through Jalis with star-shaped and hexagonal flower-like patterns.

The Taj Mahal was started after the death of Shah Jahan’s main wife Mumtaz Mahal in 1632 and completed in 1648. In the mausoleum, built entirely of white marble, the floral patterns of the Jalis fulfill their decorative task of surface design together with the marble inlays in Pietra-dura technique, which is called in India Parchin kari . Screens are alternated with stripes of jalis and mosaics of gemstones , and even the larger forms of jalis have been filled with realistic floral mosaics. The mastery of the surface through complete ornamental design (referred to in art history as horror vacui ) is a feature of Central Asian and Arabic architecture and calligraphy and symbolic expression of power.

Jalis of wood and stone at Indian palaces and townhouses

In addition to the task of creating a sacred space and designing an ornament as an ornament, Jalis provide for a non-visible living area protected from the outside world and adapt the building to the climatic conditions through the control of sun and wind. The Jalis, developed at the early Indian temples, were adopted by Muslims and Hindus in secular architecture.

In the northern Indian upper class of both religious communities, there was a secluded, reserved for women part of the house, which is referred to in India as zenana , similar to the Ḥarām Arab countries. The system of segregation was based on the idea of Parda (literally “curtain”). In addition to gender segregation, there was an extensive code of honor for distinguished women who seldom moved outside the home. Jalis could take on the role of a “curtain” and allow them to observe a public event without being seen. They served within the building as a visual screen to the area of men ( mardana ). Behind these Jalis, the women – mostly in the upper floors – could follow the official events ( darbar ). In the palaces of Rajasthan , these screens consisted of only five centimeters thick sandstone slabs, which were sawed out to fine geometric lattices. Often they represented vases out of which plants grow out: a tree of life as the ancient Indian symbol of fertility ( purnaghata ).

The best known example of a palace for women is the Hawa Mahal , “Palace of the Winds”, in Jaipur from 1799. The façade to the street side consists of closely adjacent, semi-circular emerging from the surface, with Bengali roof forms ( bangaldar ) bayed , the overall to give a living structure. The name refers to the honeycomb jalis in these jarokas , which allow the wind to pass freely. The five-storey reddish-sandstone building did not serve as a residential palace, but allowed the ladies to watch the festivities in the central square. The upper three floors consist only of the rooms in the facade and staircases and platforms behind them.

Firmly installed jalis were used in palaces as a 45-centimeter-high barrier that fenced in the seat of an authority figure or a throne, thus demarcating them during an audience of petitioners.

Round-shaped and intricately designed wooden jalis are preserved in western India, especially in Gujarat and Rajasthan, at townhouses of merchants and landowners of the 19th century. In the hot and dry climate, these Haveli housing units are adapted by inner courtyards, heat-retaining thick massive walls and shady windows. In addition come to over 3.5 meters high rooms and pillared vestibules that serve during the day and in the rain as a residence. Jalis and wooden windows ( jarokas ) are closed during the day because of the heat and because of sand winds through thick wooden shutters. At night they are opened to let cool air through. In the desert city of Jaisalmer , the Havelis have up to half-meter-thick walls made of light yellow, seamless sandstone blocks and in the upper levels of five centimeters thick limestone slabs made of jalis with geometric patterns on the windows and balcony railings.

The late medieval handicraft center for woodworking in northwestern India lay in Patan (Gujarat). The brightly painted wood carvings took on Islamic motifs and copied the stone sculptures in the Jain temples of Gujarat, especially the 11th century. The traditional wooden jarokas of the townhouses rise out of the façade in a semicircular or polygonal shape and are supported by struts that emerge from a console . For the construction of the house and for the decorative elements mainly cypress or cedar wood was used. The finest, sculpted leaf tendrils and floral motifs can be seen on the balconies, doors and windows of the first floor, while for the openings on the ground floor for safety reasons in younger houses metal grids were used.

The Punjab region in present-day Pakistan has produced a relatively little-known regional architectural style, which developed in the Lahore and Multan cultural centers and continued to retain indigenous Indian features after the arrival of the Central Asian Islamic Ghaznawids in the 11th century. Especially in the architecture of residential buildings and palaces alien rulers adapted to the Indian styles and building traditions, as defined in the Shilpa Shastras (ancient Indian treatises on architecture). An essential stylistic element was wooden window grilles, which basically did not consist of turned elements, but were similar to the stone jalis cut from solid wood panels. These latticeworks, made up of small- patterned star-shaped basic patterns, were made in Punjab Pinjra or Mauj and were made up to the beginning of the 20th century. The other method of putting together individual wooden slats was also used in the Punjab.

In wooded Kashmir , wood was the traditional building material for houses and palaces. The local architectural style has produced multi-storey verandas on the houses, cantilevered roofs and turned jalis on the balcony railings and shutters. At the Khanquah (home of a Sufi people and meeting center for its devotees, see Tekke ) by Shah Hamadan in Srinagar , which dates back to the 15th-17th centuries according to its style and original purpose, the walls consist of layers of unconnected wooden beams, whose interstices are filled with bricks. The windows are designed by Jalis from narrow wooden sticks in hexagonal and fan-shaped patterns. The latter forms could go back to Buddhist influence in today used as a mosque building.

Modern use of Jalis

The climatic advantages of jalis, sunshades ( chujjas ) or windows ( jarokas ) have been revisited by some architects in the 20th century. The grid of concrete prefabricated by Le Corbusier at his secretary’s office of Chandigarh or at the local Palace of Justice (completed in 1955) built the window facades take over the principle of the Jalis by providing shade and guiding the wind.

A movement within modern architecture in India since the second half of the twentieth century, in a return to Indian traditions, no longer uses only Indian elements of form as a copy for decoration, but tries to integrate them into their original function. The Indian architect Raj Rewal placed shadows in narrow grids in front of the façades, whose function is derived from Jalis, at several of his clay-brown exposed concrete public buildings and housing estates.

The social architecture of Laurie Baker combined the tradition with a cost-effective design, using partially used materials. The result is buildings with openwork brick walls in the manner of Jalis, whose openings serve to ventilate and create dramatic light and shadow effects in the interior.

Even outside of India, architects rely on the tradition of the Jalis, regardless of the traditional forms and only partially with the same functions large projects as a hotel in Dubai are designed. In representational architecture as in the 2001 built Indian Embassy in Berlin Jalis are deliberately used as a symbol of traditional Indian craftsmanship, which refers to the return to the palace architecture from the time of the Mughal Empire on a period of stability and prosperity of India.

Further names

During the Mamluk era (1250-1517), Roshan (Rushan, Rawashin) referred to traditional wooden windows throughout the Islamic world. Later, regionally different names have become common. Thus, there are forms of Jalis outside the Indian cultural area under the widespread term Maschrabiyya also in the Middle East and North Africa. In the narrower sense, there are Maschrabiyyas in Egypt and the rest of North Africa, while with Roshan specifically the bay windows at the trading houses of the port cities on the Red Sea as Jeddah and Sawakin are called. In Iraq , Jalis Shanashil and in Syria Koshke . The last word is Arabic كشك , DMG košk , means in Turkish köşk, from which the German word Kiosk derives and originally meant a partly open on the sides garden pavilion, which was elaborately decorated with carved wooden windows. The Turkish influence during the Ottoman Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries brought summer houses ( kushk ) in which the women could see through the windows, without being seen, in the palace gardens of Yemen .

Production of the stone jalis

The perforation of the Jali requires due to the high risk of breakage of thin stone slabs a high handicraft skill. As stone material previously only soft rocks such as marbles and sandstones were used; Hard rock can only be used since the use of water jet systems to cut out the patterns from the rock.

Historical production

The jali is made either by perforating a massive stone slab or by inserting stone grid elements. In the case of the precious Jalis of the time, the Mughal rulers also used incrustations with gemstones .

The original production of Jalis was purely handmade. The craftsmanship of the stone processing by Indian stonemason tempted the possibilities of mechanical processing of the stone material to the limits of its capacity. A faulty push or wrong operation, and the Jali could split into splinters. In order to shape the patterns, hand-driven drills were used, as well as files and rasps, mostly very simple but specially and individually made tools. Partial water was added to cool and optimize the tooling. The historic production and fitting of the differently colored stone materials and gemstones that were inserted, required an equally high mastery of craftsmanship. If a polish of the stone surfaces is to be produced, then marble had to be used for the jali, since there are only a few sandstones that take on a partial polish.

Production with water-jet cutting technology

With the introduction of water jet cutting machines in the late 1990s, Jali molds can be cut out of natural stone slabs by means of a water jet with pressures up to 6000 bar and discharge speeds at the nozzles of up to 1000 m / s. The water jet are mixed to optimize its cutting action abrasives such as granules . These machines are CNC controlled , and the patterns are drawn with support from CAD systems .

In particular, the construction boom in the Arab countries has led to increased use of Jali ornamentation and the increased use of water jet systems. However, the exclusive Jali panels, made with the most up-to-date technology, do not achieve the liveliness, originality and effect of the raised and recessed surfaces and cross-sectional profiled bars of historic Jalis. The earlier craftsmanship created unique artifacts .

Source From Wikipedia