The Russian Revival style is the generic term for a number of different movements within Russian architecture (pseudo-Russian style, neo-Russian style, Russian-Byzantine style/Byzantine style (Russian: псевдорусский стиль, неорусский стиль, русско-византийский стиль)) that arose in second quarter of the 19th century and was an eclectic melding of pre-Peterine Russian architecture and elements of Byzantine architecture.

The Russian Revival style arose within the framework that the renewed interest in the national architecture, which evolved in Europe in the 19th century, and it is an interpretation and stylization of the Russian architectural heritage. Sometimes, Russian Revival style is often erroneously called Russian or Old-Russian architecture, but the majority of Revival architects did not directly reproduce the old architectural tradition. Being instead a skillful stylization, the Russian Revival style was consecutively combined with other, international styles, from the architectural romanticism of first half of the 19th century to the modern style.

Terminology

The terms denoting the direction in the Russian architecture of the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, connected with the search for an original national style, are still inaccurate, and individual phenomena that existed within the framework of this direction are not differentiated .

Appearing at the beginning of the 19th century, the name “Russian-Byzantine style”, which was often reduced by contemporaries to “Byzantine style”, denoted such different samples of nationally oriented architecture as “Tone architecture” (according to KA Ton ), which has nothing in common with Byzantine prototypes, and, for example, constructions imitating the samples of the Caucasian and Balkan architecture . The term “Russian style” that appeared in the second half of the 19th century united even more diverse phenomena – from small court country buildings of the 1830s in the “Peyzan style”, idealizing the way of life of the peasantry, to massive wooden park buildings and exhibition pavilions of the 1870s, and also large public buildings of the 1880s .

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the whole aggregate of phenomena in the architecture of the nineteenth century, associated with the search for Russian national identity, was called the “pseudo-Russian style” (the term V. Ya. Kurbatov ) – in contrast to the “neo-Russian style”. Along with the definition of “pseudo-Russian”, already having an evaluative character, the name with an even more negative tint – “false Russian style” began to be used to denote the same phenomena.

The question of the genesis of the “neo-Russian style” (another name – Novorussky) is controversial. EI Kirichenko, AV Ikonnikov and a number of other authors consider the Neo-Russian style as a “direction”, “option” or “national-romantic branch” of modernity . In the opinion of DV Sarabyanov, the Neo-Russian style existed as a variant within modernity, although it made attempts to gain independence . MV Nashchokina and EA Borisova believe that the neo-Russian style and modernity can not be identified . EI Kirichenko differentiates the neo-Russian style, as the direction of modernity, and the Russian style, as one of the architectural trends of eclecticism, at the level of differences between the architects’ interpretation of the samples of the domestic architecture and the methods of form-building used by them:

Styling is characteristic of modernity in contrast to eclecticism, for which stylization is typical. <...> Stylistics is based on visually authentic (realistic) recreation of the heritage of the past. <...>… provides the possibility of using any form of architecture of the past in any combination. In stylization, the attitude toward the sample is different. Artists are interested in the general, the nature of the interconnection of elements and forms, the whole, and not the detail, particular. General features and recognizability of the sample are preserved. However, the samples themselves, when reconstituted, are transformed in accordance with new tastes. <...> This is done without any desire for historical authenticity and accuracy of reproduction of sources .

DV Sarabyanov believes that architecture researchers fairly share Russian and Neo-Russian styles: ” Indeed, the border between them is a line dividing eclecticism and modernity ” .

Features of the style

Russian-Byzantine style

One of the first trends that emerged within the framework of the pseudo-Russian style was the “Russian-Byzantine style” that originated in the 1830s in the architecture of churches. The first example of buildings in this style is the Orthodox Church of Alexander Nevsky in Potsdam, designed by Vasily Stasov. The consecration of the temple occurred in September 1829 .

The development of this direction was facilitated by very broad government support, since the Russian-Byzantine style embodied the idea of official Orthodoxy about the continuity between Byzantium and Russia . For Russian-Byzantine architecture is characterized by the borrowing of a number of compositional techniques and motifs of Byzantine architecture, most vividly embodied in the “exemplary projects” of the churches of Constantine Ton in the 1840s. The Cathedral of Christ the Savior, the Grand Kremlin Palace and the Armory Chamber in Moscow, as well as cathedrals in Sveaborg, Yelets ( Ascension Cathedral ), Tomsk, Rostov-on-Don and Krasnoyarsk were built in the tone.

Imitation of Old Russian architecture

For another direction of the pseudo-Russian style that arose under the influence of Romanticism and Slavophilism, buildings with arbitrary interpretation of the motifs of Old Russian architecture are typical . One of the first Russian architects who turned to historical layers, Mikhail Dormidontovich Bykovsky said :

Cultural background

Like the romantic revivals of Western Europe, the Russian revival was informed by a scholarly interest in the historic monuments of the nation. The historicism resonated with the popular nationalism and pan-Slavism of the period. The first illustrated account of Russian architecture was the project of Count Anatole Demidov and French draughtsman André Durand, the record of their 1839 tour of Russia was published in Paris in 1845, as Album du voyage pittoresque et archaéologique en Russie. Durand’s lithographs betray a foreigner’s sensitivity to the seeming otherness of Russian architecture, displaying some curiously distorted features, and while they are, on the whole, fairly accurate representations, the folios that he produced belong to the genre of travel literature rather than historical inquiry. The attempt to discern the chronology and development of Russia’s building begins in earnest with Ivan Snegirev and AA Martynov’s Russkaya starina v pamyatnikakh tserkovnago i grazhanskago zodchestva (Moscow, 1851). The state took an interest in the endeavour by sponsoring a series of folios published as Drevnosti rossiiskago gosudavstva (Moscow 1849-1853, 6 vol.) depicting antiquities and decorative works of art. By this time the Moscow Archaeological Society undertook research on the subject, formalising it as a field of study. A series of triennial conferences was instituted from 1869 to 1915, and its reports included studies of the architecture of the Kievian Rus’ and early Moscow periods. Perhaps the Society’s most significant achievement was the publication of the Kommissii po sokhraneniiu drevnikh pamyatnikov in 6 volumes between 1907 and 1915. Also the St. Petersburg Academy of fine Arts commissioned research from VV Suslov in the form of his two multi-volume works Panyatniki drevnyago russkago zodchestva (1895–1901, 7 vol.) and Pamyatniki drevne-russkago iskusstva (1908–1912, 4 vol.). With the application of positivist historical principals the chronology of Russian architecture was firmly established by the time of the publication of that definitive 6-volume survey of Russian art Istoriya russkogo isskustva (1909–1917), edited by Igor Grabar, the appearance of the final volume was, however, interrupted by the revolution.

Development

1825-1850

The first extant example of Byzantine Revival in Russian architecture and the first example ever built, stands in Potsdam, Germany, a five-domed Alexander Nevsky Memorial Church by Neoclassicist Vasily Stasov (builder of neoclassical Trinity Cathedral, St. Petersburg, father of critic Vladimir Stasov). Next year, in 1827, Stasov completed a larger five-domed Church of the Tithes in Kiev.

The Russo-Byzantine idea was carried forward by Konstantin Thon with the firm approval by Nicholas I. Thon’s style embodied the idea of continuity between Byzantium and Russia, perfectly matching the ideology of Nicholas I. Russian-Byzantine architecture is characterised by mixing the composition methods and vaulted arches of Byzantine architecture with ancient Russian exterior ornaments, and were vividly realised in Thon’s ‘model projects’. In 1838, Nicholas I “pointed out” Thon’s book of model designs to all architects; more enforcement followed in 1841 and 1844.

Buildings designed by Thon or based on Thon’s designs were Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, the Grand Kremlin Palace and the Armoury in Moscow, also cathedrals in Sveaborg, Yelets, Tomsk, Rostov-on-Don and Krasnoyarsk.

Official enforcement of Byzantine architecture was, in fact, very limited: it applied only to new church construction and, to a lesser extent, to royal palaces. Private and public construction proceeded independently. Thon’s own public buildings, like the pseudo-Renaissance Nikolaevsky Terminal, lack any Byzantine features. A closer look at churches constructed in Nicholas reign reveals many first-rate neoclassical buildings, like the Elokhovo Cathedral in Moscow (1837–1845) by Yevgraph Tyurin. Official Byzantine art was not absolute in Nicholas reign; it is scarce in our days, as the Byzantine churches, declared ‘worthless’ by Bolsheviks, were the first to be demolished in the Soviet era.

1850s

Another direction taken by the Russian Revival style was a reaction against official Thon art, influenced by romanticism, Slavophilism and detailed studies of vernacular architecture. The forerunner of this trend in church design was Alexey Gornostaev (in his later years, 1848–1862), notable for reinventing Northern Russian tented roof motif augmented with Romanesque and Renaissance vault structure. An early extant example in civil architecture is the wooden Pogodinsky cottage in Devichye Pole, Moscow, by Nikolai Nikitin (1856).

Post-1861

The Emancipation reform of 1861 and subsequent reforms of Alexander II pushed the liberal elite into exploring the roots of national culture. The first result of these studies in architecture was a birth of “folk” or Pseudo-Russian style, exemplified by 1870s works of Ivan Ropet (Terem in Abramtsevo, 1873) and Viktor Hartmann (Mamontov printing house, 1872). These artists, in alliance with Narodnik movement, idealized the peasant life and created their own vision of “vernacular” architecture. Another factor was the rejection of western eclectics that dominated civil construction of 1850s-1860s, a reaction against “decadent West”, pioneered by influential critic Vladimir Stasov.

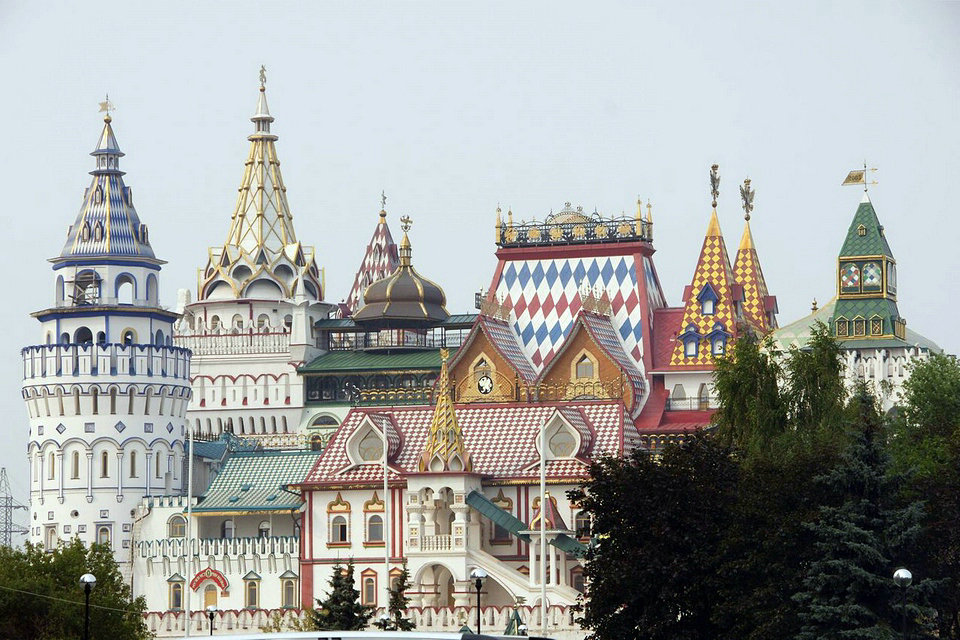

Ivan Zabelin, a theorist of the movement, declared that “Russian Khoromy, grown naturally from peasants’ log cabins, retained the spirit of beautiful disorder… Beauty of a building is not in its proportions, but on the contrary, in the difference and independence of its parts” (“русские хоромы, выросшие органически из крестьянских клетей, естественно, сохраняли в своем составе облик красивого беспорядка… По понятиям древности первая красота здания заключалась не в соответствии частей, а напротив в их своеобразии, их разновидности и самостоятельности”). As a result, “ropetovschina”, as Ropet’s foes branded his style, concentrated on hoarding together vivid but not matching pieces of vernacular architecture, notably high-pitched roofs, barrel roofs and wood tracery. Wood was the preferred material, since many fantasies could not be physically built in masonry. This was good and bad for “dopetovschina”. Bad, because wooden structures, especially those unconventionally shaped, were not scalable and had a very short life span. Very few survive to date. Good, because speed of construction and unorthodox looks were a perfect match for exhibition pavilions, coronation stands and similar short-term projects. The trend continued into 20th century (Fyodor Schechtel) and 1920s (Ilya Golosov).

For a short time in the 1880s, a less radical version of Pseudo-Russian style, based on copying 17th century brick architecture, almost succeeded as the new official art. These buildings were built, as a rule, from the brick or whitestone, with the application of modern construction technology they began to be abundantly decorated in the traditions of Russian popular architecture. The characteristic architectural elements of this time, such as “pot-bellied” columns, low arched ceilings, narrow window-loop holes, tented roofs, frescoes with floral designs, use of multicolored tiles and massive forging, are manifest both in the external and in the internal decoration of these structures. A typical example is the Historical Museum (1875–81, architect Vladimir Sherwood) which completed the ensemble of Red Square.

At the end of the 19th century

In the early 1870’s populist ideas aroused in the artistic circles increased interest in folk culture, peasant architecture and Russian architecture of the XVI – XVII centuries . One of the most striking buildings of the pseudo-Russian style of the 1870s was the Terem of Ivan Ropet in Abramtsevo near Moscow (1873) and the Mamontov printing house (1872) in Moscow, built by Victor Hartmann . This direction, actively promoted by the famous art critic Vladimir Stasov, spread first in the architecture of wooden exhibition pavilions and small town houses, and then in monumental stone architecture. By the beginning of the 1880s the “ropetovshchina” was replaced by a new official direction of the pseudo-Russian style, almost literally copying decorative motifs of Russian architecture of the XVII century. Within the framework of this direction, the buildings, built, as a rule, from brick or white stone, began to be richly decorated in the traditions of Russian folk architecture . This architecture is characterized by “pot-bellied” columns, low vaulted ceilings, narrow window-loopholes, teremoobraznye roofs, frescoes with floral ornaments, the use of multi-colored tiles and massive forging . Within the framework of this direction, the Upper Trade Rows (now the GUM building, 1890-1893, the architect Alexander Pomerantsev ), the building of the Historical Museum (1875-1881, architect Vladimir Sherwood ), completed the Red Square ensemble in Moscow, and the Savvinsky farmstead of the architect Ivan Kuznetsov. According to the sketches of the artist V.M. Vasnetsov in the Abramtzevo park in 1883, the “Hut on chicken legs” was built , in 1899-1900 – the house of IE Tsvetkov on the Prechistenskaya embankment of the Moskva River (d. 29), the Tretyakov Gallery in Lavrushinsky Lane, his own artist’s house in the 3 rd Trinity Lane of Moscow .

At the beginning of the 20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, the ” neo-Russian style ” was being developed (among architects of architecture there is no consensus as to whether this branch of the pseudo-Russian style should be singled out as an independent one ). In search of monumental simplicity, the architects turned to the ancient monuments of Novgorod and Pskov and to the traditions of the architecture of the Russian North. On the constructions of this direction sometimes there is an imprint of stylization in the spirit of the Northern Art Nouveau. In St. Petersburg, the “neo-Russian style” found its application mainly in the church buildings of Vladimir Aleksandrovich Pokrovsky, Stepan Krichinsky, Andrei Petrovich Aplaksin, Herman Grimm, although in the same style some apartment houses were built (a typical example is the Cooperman house built by the architect A. L. Lishnevsky on Plutalova Street ).

According to the sketch of SV Malyutin in 1903, the facade of the Russian Starina Museum in Smolensk was decorated. Often Malyutin conformed to the style of decorating the interior with furniture with carvings and paintings (the house of Pertsova in Moscow) .

A curious example of the neo-Russian style (with features of modernity) is the Church of the Savior of the Holy Face in Klyazma, built in honor of the 300th anniversary of the Romanovs by the architect V. I. Motylyov according to the drawing of SI Vashkov (1879-1914) – Vasnetsov’s pupil, in 1913-1916 years.

Petersburg architecture in the style is marked by the work of the architect AA Bernardazzi – the apartment house of PK Koltsov (1909-1910) on the corner of the English avenue and the Officer’s street (now Dekabristov Street), which was popularly called ” The Tale House ” (destroyed in Second World War ).

The Russian pavilions designed by Shekhtel at the international exhibition in Glasgow in 1901 ( English ) became widely known. He also designed the facade of the Yaroslavl station in Moscow .

Historians of architecture expressed the opinion that the Neo-Russian style is closer to modernity than to historicism, and this differs from the “pseudo-Russian style” in its traditional sense .

1898-1917

At the turn of the centuries, the Russian Orthodox Church experienced a new trend; construction of unusually large cathedrals in working-class suburbs of big cities. Some, like Dorogomilovo Ascension Cathedral (1898–1910), rated for 10,000 worshippers, were launched in quiet country outskirts that increased in population by the time of completion. Christian theorists explain the choice of such remote locations with the desire to extend the reach of Church to working class, and only working class, in the time when wealthier classes stepped away from it. Byzantine architecture was a natural choice for these projects. It was a clear statement of national roots, against the modern European heresies. It was also much cheaper than grand Neoclassical cathedrals, both in initial costs and subsequent maintenance. The largest examples of this type were all completed after the Russian revolution of 1905:

Dorogomilovo Cathedral, Moscow, 1898–1910

Our Lady of Iveron Cathedral in Nikolo-Perervinsky Monastery Cathedral, Pererva (now Moscow) 1904-1908

Kronstadt Naval Cathedral, 1908–1913

1905-1917

Rogozhskoye Cemetery belltower by Fyodor Gornostaev, 1908–1913

Balakovo church by Fyodor Schechtel, 1909–1912

Emperor railway station in Pushkin town, 1912

St.Nicholas church by Belorusskaya Zastava in Moscow, 1914–1921

Source From Wikipedia