In the 20th century woodblock printing was revived in new contexts These ranged from the meticulous if sterile reproduction of famous works of art to the sōsaku hanga (‘creative prints’) movement, in which the artist was responsible for all stages of print production, including design, block-cutting and printing From 1915 to 1940, a neo-ukiyoe style ran parallel with the sōsaku hanga movement The neo-ukiyoe movement was based on publishers contracting artists, block-cutters and printers to produce prints of women, actors and landscapes for a largely foreign clientele These prints were issued in numbered, limited editions and were intended for an exclusive audience The contrast with Edo-period prints could not have been greater

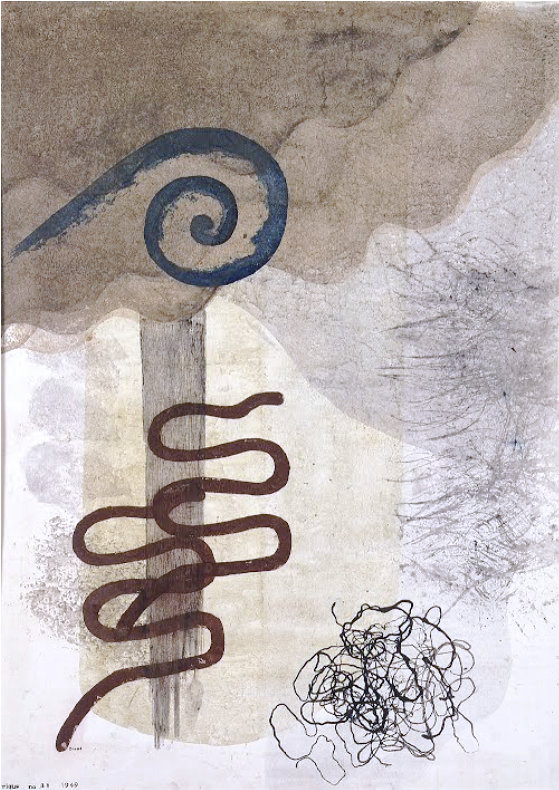

Sōsaku-hanga (創作版画? “creative prints”) was an art movement in early 20th-century Japan It stressed the artist as the sole creator motivated by a desire for self-expression, and advocated principles of art that is “self-drawn” (自画 jiga), “self-carved” (自刻 jikoku) and “self-printed” (自刷 jizuri) As opposed to the shin-hanga (“new prints”) movement that maintained the traditional ukiyo-e collaborative system where the artist, carver, printer, and publisher engaged in division of labor, creative print artists distinguished themselves as artists creating art for art’s sake

[pt_view id=”6981220xay”]

The birth of the sōsaku-hanga movement was signaled by Kanae Yamamoto’s (1882–1946) small print Fisherman in 1904 Departing from the ukiyo-e collaborative system, Kanae Yamamoto made the print solely on his own, all the way from drawing, carving and printing Such principles of “self-drawn”, “self-carved” and “self-printed” became the foundation of the creative print movement, which struggled for existence in prewar Japan along with other art movements, and gained its momentum and flourished in postwar Japan as the genuine heir of the ukiyo-e tradition

The 1951 São Paulo Art Biennial witnessed the success of the creative print movement Both of the Japanese winners, Yamamoto and Kiyoshi Saitō (1907–1997) were printmakers, who outperformed Japanese paintings (nihonga), Western-style paintings (yōga), sculptures and avant-garde Other sōsaku-hanga artists such as Kōshirō Onchi (1891–1955), Un’ichi Hiratsuka (1895–1997), Sadao Watanabe (1913–1996) and Maki Haku (1924–2000) are also well known in the West

The creative print movement was one of the many manifestations of the rise of the individual after decades of modernization In both artistic and literary circles, there emerged at the turn of the century expressions of the “self” In 1910, Kōtarō Takamura’s (1883–1956) “A Green Sun” encourages artists’ individual expression: “I desire absolute freedom of art Consequently I recognize the limitless authority of individuality of the artist Even if two or three artists should paint a “green sun”, I would never criticize them for I myself may see a green sun” In 1912, in “Bunten and the Creative Arts” (Bunten to Geijutsu), Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916) states that “art begins with the expression of the self and ends with the expression of the self” These two essays marked the beginning of the intellectual discussion of the “self”, which immediately found echo in the art scene 1910 witnessed the first publication of a monthly magazine called White Birch (Shirakaba), the most important magazine shaping the thought of the Taishō period Aspiring young artists organized its first exhibition in the same year Shirakaba also sponsored exhibitions of Western art

In its early formative years, the sōsaku-hanga movement, like many other art movements such as the shin-hanga movement, futurism and proletarian art movement, struggled to survive, experiment and sought a voice in an art scene dominated by mainstream arts that were well received by the Bunten Hanga in general (including shin-hanga) did not achieve the status of Western oil paintings (yōga) in Japan Hanga was considered as a craft that was inferior to paintings and sculptures Ukiyo-e woodblock prints had always been considered as mere reproductions for mass commercial consumption, as opposed to the European view of ukiyo-e as art, during the climax of Japonisme It was impossible for sōsaku-hanga artists to make a living by just doing creative prints Many of the later renowned sōsaku-hanga artists, such as Kōshirō Onchi (also known as the father of the creative print movement), were book illustrators and wood carvers It was not until 1927 that hanga was accepted by the Teiten (the former Bunten) In 1935, extracurricular classes on hanga were finally permitted