Project: Complexion and Significance – The Human Image in Panel Painting from 200 to 1250 in the Mediterranean

Today, the panel painting characterizes our understanding of the medium of painting, with the representation of human beings being one of its most important tasks. The technical requirements, conditions and the limiting factors that led to the start of panel painting and its further development are the subjects of this interdisciplinary and epoch-spanning research project. The history of the development of the panel painting will be scrutinized by examining representative examples from antiquity, the early and high Middle Ages. The project focuses on the execution of flesh tones: Which techniques were chosen in order to achieve certain effects at particular times? How was traditional knowledge from antiquity adapted? Is there any correlation between technique and either the function or the original location of a painting? How are social changes and ideological shifts reflected?

Italy:

Opificio delle Pietre Dure (Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali), Florence

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Museo Nazionale di Villa Guinigi, Lucca

Museo Nazionale di San Matteo, Pisa

Musei Vaticani, Cittá del Vaticano

Monastery Santa Maria del Rosario, Monte Mario, Rome

L’Istituto Superiore per la Conservazione ed il Restauro, Rome

Germany:

Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Antikensammlung und Rathgen-Forschungslabor, Berlin

Akademisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn

Liebieghaus, Skulpturensammlung, Frankfurt a. M.

Diözesanmuseum, Freising

Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, München

Martin von Wagner Museum, Würzburg

Egypt:

Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai

All the panel paintings were documented in high resolution using various photographic methods – VIS photography, raking light photography, UV fluorescence photography and infrared photography. The example of the icon with the Crucifixion of Christ (Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai, 47 x 25 x 1 cm) shows how different kinds of information were revealed and documented.

The use of the pigment Egyptian Blue was detected on mummy portraits by means of an infrared filter (VIL photography). Egyptian blue is one of the oldest, artificially produced colorants.

The pigment luminesces in the VIL image: the green of the wreath is a mixture of Egyptian blue and yellow colorant. The whites of the eyes were shaded with Egyptian Blue. The garment also contains Egyptian Blue.

A portable stereomicroscope was used on site to examine the complex paint layers of the panel paintings in microscale.

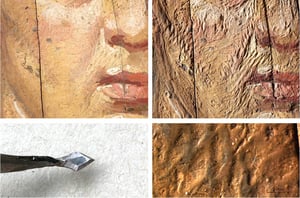

To clarify the layer sequence, a tiny piece of paint is taken, embedded in resin, cut and polished transversely across the layers. In cross-sections one sees the layer sequence of the painting. The layers are optically differentiated by means of various light microscopic examination methods. The elements of the colorants can be analyzed by a scanning electron microscope (SEM).

During the 19th century, travelers, dealers, and early Egyptologists brought a large number of so-called portrait mummies to the attention of European collectors. They were interested mainly in the painted portraits rather than in the bulky embalmed bodies. Consequently, in today’s museums one mostly finds only the cut-out portraits of the deceased. The portrait mummy trend arose in the oases of Egypt during the Imperial Roman era, from the 1st century to the 3rd century, under Greek influences.

All of the mummy portraits examined in the ISIMAT project are from German museums. They were selected for their painting techniques or iconographical aspects and were examined under similar conditions. The mummy portraits show men, women and children.

Based on visual characteristics, the examined antique panel paintings could be attributed to three painting techniques: the Antique Tempera Technique, the Encaustic and the Antique Cold Wax Painting.

Water based binders such as egg, glue or gums were used in the Tempera Technique. These colors were usually applied thinly. In addition to the Tempera Technique, beeswax was also used as a binder.

When painting with beeswax, one can distinguish at least two separate techniques.

The Cold Wax Painting is different from the Encaustic, mainly because it alone shows brushstrokes, and there is no recognizable reworking with heat in the painting process.

The encaustic mummy portraits show both brushstrokes and traces from heated tools. A surface relief of ‚melted‘ and pasty-solidified color textures indicates that the paint layer was processed with heat. Different forms of so-called “cauteria” were observed in raking light.

The so-called Severan Tondo is the only known panel painting from Antiquity that depicts an imperial family. The Tondo came – like the mummy portraits – from Egypt and shows the emperor Septimius Severus (193–211) with his wife Julia Domna and their sons Geta and Caracalla. The face of Geta was scratched out by order of his brother. Painted portraits like this existed in high numbers in Antiquity and hung in offices, shops and also sanctuaries.

The so-called Severan Tondo, painted in Antique Tempera Technique, shows a vibrant, fast and experienced approach to painting. Bright shades were used over dark ones and reversed. The modeling of the flesh tones was achieved by overlapping and juxtaposing numerous layers of translucent paint. Thin glazes were added on top of impasto brushstrokes late in the painting process – they let the earlier layers shine through, so that the superimposition creates additional shades and at the same time induces volume and plasticity.

Schematic representation of the paint layers of an eye in Antique Tempera Technique, using the example of: Mummy portrait of a man (2nd half of the 2nd century – around 200), Würzburg, Martin von Wagner-Museum, Inv. H 2196.

Sources on painting techniques in AntiquityWritten sources on painting techniques in Antiquity allow us to assume the following: As tools painters used the brush (“penicillum”), a “cauterium” (a metal spatula that can be heated), a “thermastris” (a fire source to heat the “cauterium”) and for storage: shells, small pottery bowls or paint boxes.The only archaeological finds that can be assigned without doubt to painters come from graves and from Pompeii. One of the most impressive grave inventories from a (fresco) painter is from Hawara, which is today in the British Museum in London. No grave inventory has been ascribed to a panel painter yet.

How did ancient painters paint with wax? To answer this question, experimental reconstructions of the painting technique with beeswax were conducted.Wax paints in different shades were fused or mixed on a wooden panel with a heated metal spatula.In order to produce long and uniform brushstrokes, as observed in mummy portraits, the wax had to be made “liquid” – various processing possibilities are conceivable.

Schematic Diagram for the Purification and Pretreatment of Beeswax

Recipes in ancient sources, e.g. by Pliny the Elder (Naturalis historia, 1st century) or Dioscorides (De materia medica, 1st century), served as the basis for the reconstructions.

The descriptions in the sources leave much room for interpretation; for example, when boiling wax with seawater and lye different end products can result. It is still unclear which product(s) was (were) used for painting.

Although the mummy portraits still look beautiful today, the beeswax in their paints has altered significantly after nearly 2000 years of ageing in the Egyptian climate. Gas chromatograms of fresh beeswax and beeswax from a mummy portrait reveal that the components with low boiling points have evaporated. In the gas chromatograms the individual compounds are separated by boiling point: the more volatile components appear on the left, while compounds with lower volatility appear on the right.

Because the alterations caused by ageing are superimposed over alterations induced by the Treatment described on the last slide, it is not possible today to determine with certainty which product (a, b or c) was initially used.

The Greek-Orthodox Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai in Egypt was founded in the 6th century and conserves one of the world’s oldest and largest collections of icons. Two research campaigns were carried out in 2016 and 2017 for the ISIMAT project.

For the ISIMAT project, eleven panel paintings were examined. They may be dated to between the 7th and the 10th centuries. Stylistically they belong to either the Byzantine or the local tradition. The painting technique was classified as the medieval tempera technique on the basis of optical criteria.

The panel shows the oldest known painted depiction of the dead Christ on the cross. The painter didn’t differentiate the flesh tones of the dead from the living or the male from the female figures. Obviously, his goal was to portray Christ at the moment when he overcame death more than it was to characterize the transience of his human body.

As on other early icons, brightly colored paint layers were applied directly onto the wooden panel without a white ground. The flesh tones are modeled over an ocher-colored base. Instead of gold, yellow paint containing orpiment was used. The panel originally had an applied frame that is now lost.

The composition of this preserved fragment representing the crucifixion is reduced to the main figures which are shown isolated in front of a golden ground. The painterly conception of the faces has the same quality as works attributed to the masters employed at the imperial court in Constantinople.

The flesh tones were painted on a brownish green base. Shadows were indicated with a darker green before adding the brown, pink and white layers in numerous translucent applications. This creates the effect of a three-dimensional body illuminated by natural light.

The panel, which was probably the left wing of a triptych, is one of the oldest icons preserved in the Holy Monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai. The paintings show St. Athanasius the Great (died 373), the Archbishop of Alexandria, who is considered to be one of the most influential church teachers, as well as St. Basil the Great (died 378), Bishop of Caesarea and Metropolitan of Cappadocia, who was one of three Cappadocian church fathers. St. Basil’s rules are considered to be the basis for monastic life especially in the Eastern World. Both Church teachers embody the ascetic type of a saint, characterized by elongated features and the expressive description of their physiognomy.

This icon is also painted without a white ground layer: The bright colors were applied directly onto the wooden support. For the haloes yellow paint containing ocher and large orpiment particles was used. The flesh tones were modeled using only a few colors (white, red, black a little pink) over a layer of ocher underpainting.

The Mother of God in Santa Maria del Rosario on the Monte Mario in Rome was painted in a unique, fine and high painterly quality. Her human gaze still fascinates the viewer. The paints are based on a waxy binder and were applied with a brush. The background and halo are gilded. The white gesso ground, applied only partially to the surface, served as a preparatory layer for the gilding but not the waxy paints.

The waxy, ocher- and pink-colored flesh tones were applied in layers over a green base color. The brush strokes partly cross each other, leaving the lower paint layers partly visible. The numerous flesh tones form the transitions of the delicate skin color.

Since 1613, the so-called Salus Populi Romani, has been kept in the baroque retable of the Cappella Paolina in Santa Maria Maggiore. It has been known as the Salus Populi Romani since the 19th century. The figures are rendered in front of gilded background. Furthermore, the now red halos were originally gilded. The painting was executed in Tempera Technique.

Over a green base color, the flesh is modelled with many thin paint applications by single brushstrokes. The flesh tones were omitted in sections to allow the green base layer to form the shadows, which were deepened with transparent brown paint layers. Brown, vermilion red, and white brushstrokes complete the painting.

Examinations of Panel Paintings in Tuscany. Panel paintings from Florence, Pisa and Lucca: The painting techniques used for the flesh tones of 15 panel paintings in Florence, Pisa and Lucca were examined and compared. Since painting techniques have been passed on through painting practices, the study of numerous painting methods is of great importance. They provide information about the wanderings of artists and the spread of their painting practices.

This cross-section of Christ’s flesh in an Italian crucifix reveals a complicated build-up of many layers. The ocher to white flesh tones were laid in (underpainted) with green. On top there is a varnish, which can be discerned by its bright fluorescence in UV light.

This particular stratification of colors is not representative of all flesh tones. In medieval Tuscany at least three different traditions for painting flesh tones can be observed.

In Tuscany different painting traditions can be ascertained. The methods of painting share the fact that the modeling of the flesh tones occurs over a colored base layer. This painting layer, referred to as the ‘base color’, is executed in different shades: from bright orange and yellow-pink to pink and green.

Over the base color, modeling is built up in different ocher-colored to white skin colored mixtures, light and shadow colors. The base color is left visible in places under the modeling and is thus part of the painting.

The face of Christ from the Croce di Berlinghiero, Lucca, is painted on top of a thin, bright yellowish base layer. Over this, the cheeks, forehead and chin are modeled with very fine, translucent strokes of cinnabar. Broader, opaque white brush marks form the highlights.

The delicate modeling of the face was created by layers of yellow transparent paint (glazes). The painting seems to shine as if it were executed over gilded ground.

The modeling of the flesh tones of the face of Christ on the Croce di San Sepolcro results from the double application of shadow- and light colors, as well as from the red of the cheeks over the yellow-ocher to pink base color.

This technique is based on the painting tradition described in the ‘Schedula diversarum Artium’.

Giunta Pisano modeled the face of Christ on a cold-green colored base layer. The bright, almost white skin color was painted with fine brushstrokes and applied gradually more densely from the darker to the brighter parts. Various transparent, warm-green to red-brown shadow colors create the soft and painterly transitions.

The painting technique with the cold-green base color may have been of eastern origin. It is described in the “Liber colorum secundum Magistrum Bernardum” as “incarnatura greca”. This manner of painting is first named by Cennini (early 14th century) as the modern or Italian style for painting flesh tones.

At the beginning of the 14th century, Cennino Cennini described how dead people, here the Christ patiens, may be painted without red on the cheeks.

In contrast, the red painted cheeks enliven the flesh tones of Mary and John.

While Berlinghieri built the flesh tones of the Christ vivens of his “croce dipinta” on an orange-colored base layer, he modeled the accompanying figures over a green base color.

This green tone should not be associated with the painting tradition of Giunta Pisano, but with the painting instructions provided in the “Schedula diversarum”. There it is described how the faces of pale and suffering people are to be painted on a green base color.

Cross-sections of the original painting of the St. Luke Icon from Freising (today overpainted) show a brown-green base color in the areas of flesh tones.

Flesh tones with a brown-green base color were not yet present in panel paintings in Rome and Tuscany.

This finding supports the thesis that this style of painting is rooted in a Byzantine tradition. A brown-green base color is described in the “Painter’s Book of Mount Athos” (also “Hermeneia”) by the Greek painter Dionysius of Phourna.

The painting techniques for the presentation of the flesh tones were compared to passages and instructions from selected medieval sources.

The temporal location and the spatial dissemination of painting practices, such as through the migration of the artists, are reflected not only in the works but also in the written traditions:

“Schedula diversarum Artium”, an encyclopedic art technical collection in three books from various sources, from the first half of the 12th century

“painter’s book from Mount Athos” (also “Hermeneia”) of the Greek painter Dionysius of Phourna (died after 1740), as a late summary of medieval Byzantine techniques of icon painting

“Liber colorum secundum Magistrum Bernardum quomodo debent distemperari et temperari et confici”, the painting treatise of the master Bernardo from Morimondo (Milan) from the 13th century

“Il libro dell’arte”, the famous painter’s book of Cennino Cennini, Padova, early 14th century

At least four different traditions for painting flesh tones could be distinguished in medieval panel painting.