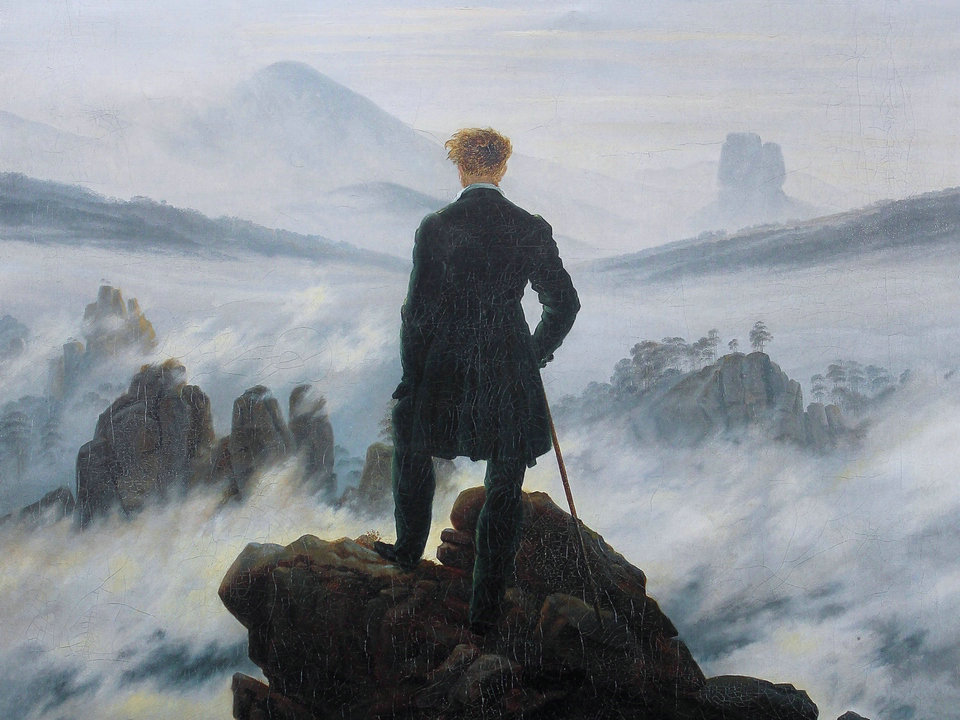

This specialized article lists the recurring themes of Romanticism in Art and Literature. Thematically, in the time of Romanticism, there was above all a renewed interest in landscape painting. The intense experience of nature and the wonder about her grandeur were central. However, landscapes were not the only thing, on the contrary. As diverse as the stylistic features of romanticism, the choice of subjects of writers and painters is also broad. In addition to imposing landscapes and vistas, for example, they frequently chose literary and historical subjects. This choice is related to the enchantment of the distant, the unknown, the imagined, as a form of escapism. Dreams and nightmares were equally desirable motifs. In addition, the “romantic view” returned in virtually all other conceivable themes in painting, from genre work to navies and from portraits to still lifes. There was no subject that was excluded, so long as it could serve as a bearer for the expression of what was called “the romantic soul.”

It is striking that the romantic painter often also took himself to the subject, melancholy musing, in mountains or ruins, sometimes in his own studio. The self-portrait then formed a confirmation of the usually created image of the not yet recognized, socially isolated genius, filled with ” weltschmerz “. An important aspect of romantic painting was the changed role of the artist himself. Romanticism meant a new style of life, a different view of the world. This manifested itself in, among other things, a great wanderlust among the romantic painters, who in particular often traveled to Italy, or also to the Rhine valley.. In a time when traveling by train was not yet the case, long trips were made, regularly even on foot. The longing for distant places underlined “the romantic desire”.

Love

In romanticism, love holds a very high place, it is idealized: “The reduction of the universe to a single being, the dilation of a single being to God, that is love” (Hugo, Les Miserable). This passionate or at least intense love is not exalted in the marriage which is only a cold and thoughtful arrangement excluding from the outset the exaltation of feelings [ ref. desired].

Nevertheless, romantic love is far from idyllic: the violence of passion is also the violence of desire; the carnal act is sometimes described as a rape or as a coupling of two beings in rut [ ref. desired]. The romantic hero sometimes takes by surprise the one he wants, but without premeditation:

“She was so beautiful, half-clad and in a state of extreme passion, that Fabrizio could not resist an almost involuntary movement. No resistance was opposed. ” (Stendhal, The Charterhouse of Parma, II, XXV).

The romantic love is thus absolute and excessive like that of Ginevra for Luigi in La Vendetta d ‘ Honoré de Balzac: The girl understood that a true love could alone disdain at this moment the vulgar protests. The quiet and conscientious expression of feelings Luigi announced somehow force and duration.

He subverts morality by its brutality, and arouses fatal jealousies by its inconstancy; a source of violent suffering and enjoyment, he sometimes smites and kills with a word, like Rosette, in ” We do not joke with love, which falls dead when the one who asks for his hand admits that he loves another. For romanticism, love is the only invincible fatality: it is one with the vital impulse in happiness, but is metamorphosed, in misfortune, into desperate passion, with its lot of abominable crimes, murders, betrayals, suicides, destruction of the loved one.

Death

In romantic drama, love and death are linked. Love stories usually end with passionate suicide, as in Victor Hugo’s “Hernani” and “Ruy Blas”. To be romantic, death is a way to get rid of all your troubles. This is the case in passionate stories where love is impossible. This death is often associated with the passage of time, which is also a major theme of Romanticism. She is present in the poems as “Sunsets couchants” by Victor Hugo, in which he discusses the immutability of nature in the face of time.

Mal of the century and melancholy

Romanticism expresses a profound malaise of men victims of an economic world where it becomes impossible to live with dignity. Musset thus denounces bourgeois materialism. The intellectual progress made by the Enlightenment is accompanied by a spiritual emptiness, a deep boredom that leads to suicide or madness (see Rolla de Musset):

” Hypocrisy is dead; we no longer believe in priests

But virtue is dying, we no longer believe in God. ”

The romantic malaise offers however, for some, an undeniable beauty accompanied by a happiness:

” Melancholy is a twilight. Suffering melts into a dark joy. Melancholy is the happiness of being sad. ” (Hugo, The Toilers of the Sea, III, II, I)

As for the woman, she is a distinctive sign that reinforces her power of seduction and fully expresses femininity:

“Flat-waisted women are devoted, full of finesse, inclined to melancholy: they are better women than others. »(Balzac, The Lily in the Valley)

But above all else, in French Romanticism, melancholy is the distinctive sign of the artist: it is already spleen (see Baudelaire later) without a precise cause, a morbid state where one no longer bears, where loneliness is a hell, where the consciousness of passing time, the misery of man, or the cruelty of nature overwhelm the spirit and inspire him with temptations of political revolt or suicide, unless he dark in madness. This evil is related to the human condition, and this experience of painis inseparable from life and its learning; it is a fatality that must be expiated, a punishment staged during our passage on earth.

Some romantics, including the Danish philosopher Kierkegaard, make a distinction between pleasure and happiness. These two principles, often confused since Antiquity, where happiness is considered the maximum mathematical pleasure, are differentiated by the romantic, who does not find happiness in pleasure, quite the contrary. As we see in Stendhal, the romantic hero is bored with pleasures, among women, luxury, games. For him, only the inaccessible has value, and that is why he finds true happiness only in the absence of pleasure: Julien Sorel, like Fabrice Del Dongowill only be happy in prison, the one condemned to death and the other in love with a girl whom he sees from a distance without any hope of ever being able to reach him. Thus, romanticism is very much opposed to reason: the romantic is a lucid and unreasonable hero, and who takes pleasure in being, because he finds beauty or philosophical interest only in the absurd, in what is exceeds it.

Revolt and society

The melancholy romantic translated discomfort of the individual who is unable to live in society. Romantic sensibility revolts against a political system that annihilates the artist by devoting himself to the glory of the nation. It is revolt by disgust, disgust of bourgeois greed, of modern society, disgust for a present that has neither past nor future, at once full of semblance of ruins and uncertain hopes: “we do not know, every step we make, if we march on a seed or debris., Confessions).

In this revolt, romanticism is sometimes radicalized into a hostile and denying individualism that is expressed by angry cries:

Woe to newborns!

Woe to the corner of the earth where the seed germinates,

Where the sweat of two emaciated arms falls!

Cursed be the bonds of blood and life!

Cursed family and society! (Musset, First poems)

This revolt leads to a hedonistic, sentimental morality by which the individual falls back on the pleasures of the heart. It becomes the very substance of life, to the point of leaving no alternative but revolt or death. This spirit of negation finds its most expressive incarnation in the figure of Satan (Hugo), the supreme revolt, and Mephistopheles (Goethe) the spirit that always denies. Vautrin (Balzac) who launches a challenge to the established order is called “evil like the devil”. The temptation of the fall, of the absolute revolt incarnated by Satan, fascinates the soulromantic: natural reaction of the creature against its creator, against this “ogre called God” (Petrus Borel), who is sometimes rejected in favor of the prayer (Hugo):

Lord, I recognize that the man is delirious,

If he dares to murmur;

I stop accusing, I stop cursing,

But let me cry!

For example, in “Hernani “, the hero “revolts” against the King, Don Carlos, who wants to steal Doña Sol…

Infinity and nothingness

The contemplation of nature takes in the romantic soul a metaphysical dimension which confronts it to the infinite. But it is also an inner vision, a result of sensibility that is felt rather than seen, because the infinite touches first the soul rather than the senses and is related to an intimate conviction that turn to God.

This touch of the soul reveals to man his nothingness and the weakness of his thought that makes him suffer by making him understand that he is nothing. This smallness can however be comforted by a pantheistic feeling:

And in front of the infinite for whom everything is the same,

It is as great to be a man as the sun! (Lamartine, poetic and religious harmonies)

This vision can also make the poet a magician: the infinite is thus the center of Hugo’s collection, Les Contemplations. The mind stops “distraught at the edge of the infinite”, and accesses the truths revealed to it by nature by concealing it.

The night is for the romantic sensibility a particular temporality which favors the fantasies, the dreams and the nightmares; the night is at once sweet or terrible, evokes love or death. Gérard de Nerval expresses in Sylvie the happiness of a nocturnal party: “We thought we were in paradise “.

But Charles Nodier writes, in Smarra: “It is dark!… and hell will reopen! ”

Hugo begins the epic of Satan with the poem “Et nox facta est”, which makes the night the place of damnation and the work of the fallen angel.

The ambiguous night is conducive to the evocation of the dead:

“I think of those who are no longer: Sweet light, are you their soul? ” (Lamartine, Poetic Meditations,” Le Soir “)

The light of the night, clarity lunar excites melancholy reveries where the presence of the dead is sensitive. This situation gives rise to a reminiscence that brings back memories, lost happiness, and dyes the present with the charm of the past.

Dreams and Nightmares

The dream and reverie, are central to the imagination romantic. Source of creation, daydream excites the imagination to recreate the world; it is often a melancholy and sad reverie, as Marceline Desbordes-Valmore testifies:

Sadness is dreamy, and I often dream;

Reverie brings man to meditation in the face of the great spectacle of nature: it puts him before the mysteries of existence. This “Stimmung” is close to a feeling of exile and travel: a “dark journey” from which ” poetry is born properly” (Hugo). But daydreaming is also a refuge and a bulwark against reality; for Musset for example:

Ah! if reverie was always possible!

And if the sleepwalker, extending his hand,

Did not always find the nature inflexible

Who strikes his forehead against a pillar of brass Help page on homonymy.

Reverie is thus a privileged state painful and inspiring, like the dream, sometimes sweet and enchanting, sometimes chilling and terrifying. This duality, in Nodier, makes it possible to attempt an aesthetic of the fantastic by drawing from the sources of “a fantastic likeliness or true. The fantasy dream is also found in Gautier, for example in “The Foot of the Mummy” (1840), where the reality and the dream are difficult to distinguish in the spirit of the romantic hero. It is a psychological state close to a fantastic dementia, dangerof the creator if he abandons himself to the delirium of inspiration: “He would have been able, without this fatal tendency, to be the greatest of poets; he was only the most singular of lunatics. ”

The East

The imaginary exoticism of the Orient has been pushed to its highest degrees by the representatives of the romantic current. The xix th century was accompanied by a profusion of objects and stories from all parts of the World, which fed the imaginary in Europe without having to travel there. See the article Orientalism. To read for this theme: The Orientals of Victor Hugo.

Nature

With the romantics, the theme of Nature becomes major.

Nature is, for many poets of the early xix th century, most tangible incarnation of God. It is through her that, as we see in Hugo and Lamartine, the divine best expresses his greatness. It is a place conducive to meditation, melancholy recalled by the cycle of seasons.

But for most romantics, the spectacle of Nature leads back to Man himself: autumn and sunsets become images of the decline of our lives, while the wind that moans and the sighing reed symbolize the emotions of the poet himself. Even in music, especially in Beethoven’s Pastoral, it is much less a description of rural landscapes that must be understood as the echo of serenity or anger experienced by a man. This is the landscape-state theory.

Nature, finally, is a place of rest, of recollection; in stopping there, we forget society, the worries of social life. It is also natural to the ancient spirit that trusts more easily to a lake as a friend of flesh and bones. This is the sign, at the same time, of the disdain of the Romantics for the social universe and the taste of these poets for meditation, for a return to oneself that Nature, like a mirror, only favors.

Source from Wikipedia