The Venetian Renaissance was the declination of Renaissance art developed in Venice between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

16th century

At the beginning of the sixteenth century Venice controlled a territory divided into “State of the Earth”, from the Adda to the Isonzo, and “Stato da Mar”, including Istria, Dalmatia, Ionian Islands, Crete, the Cyclades and part of the Sporades and Cyprus. The city was affirming itself as one of the most vibrant and innovative artistic centers of the peninsula, thanks also to the prosperity of commercial and mercantile activities, and to the wealth of its emporium, one of the most cosmopolitan in Europe. The general policy is now oriented towards the reconversion from a maritime empire into a mainland power, within the political balance between the Italian states. The crisis of 1509, when the city was hit by a papal interdict and the attack of the League of Cambrai, which followed the serious problems of clashes with the Ottomans in the eastern Mediterranean, was overcome thanks to a sudden overthrow of alliances and loyalty of most populations under its domains.

From a cultural point of view the city was establishing itself as a center of humanistic studies, above all thanks to the typographies that published the classical texts. To this was added a fervent interest in archeology studies, scientific data and, above all, botanical disciplines. One of the debates that animate the Venetian cultural scene of the time is that of the possibility of reconciling the ” contemplative life “, understood as a philosophical and religious speculative activity to be carried out in solitude detached from worldly events, and ” active life “”, meant as a service to the community for the achievement of the” honor. “If the great humanist Venetians of the late fifteenth tried to demonstrate the possibility of reconciliation between the two opposites, at the beginning of the new century the two tendencies seem overwhelmingly irreconcilable, giving origin of serious personal crises.

The “contemplative” practice among Venetian intellectuals favors the diffusion of particular forms of collecting, such as collections of antiquities, gems, coins, reliefs, codes, incunabula and paintings, all linked to particular cultural inclinations and characteristics of the collector. One of the most famous examples was the collection of Cardinal Domenico Grimani.

The relative freedom that the oligarchy of the Serenissima guaranteed to its citizens and visitors, was the best among those that the Italian courts could offer, and in those years it made a frequent shelter from those who had remained involved in the dangerous power games of the own states, welcoming some of the most illustrious Italian and foreign geniuses. Among the most illustrious guests were Michelangelo or the exiles of the Sacco of Rome, including Jacopo Sansovino, who settled in the city bringing the architectural innovations developed in central Italy.

Dürer in Venice

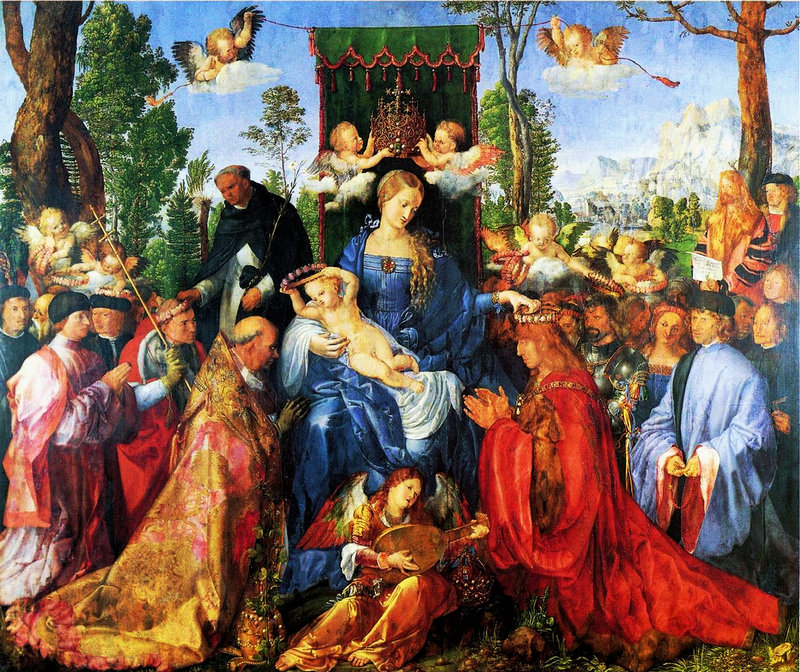

In 1505, until the beginning of 1507, the most important German painter of the time, Albrecht Dürer visited the city of Venice for the second time, after having been there in 1494 – 1495. In this second stay his fame is now very wide, thanks to a series of successful recordings throughout Europe, and the merchants of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi commission him an altarpiece for their church in Rialto, San Bartolomeo.

In the painting the German master absorbed the suggestions of the Venetian art of the time, like the rigor of the pyramidal composition with the throne of Mary at the top, the monumentality of the plant and the chromatic splendor, while the typically Nordic taste is the accurate details and physiognomy, the gestural intensification and the dynamic concatenation between the figures. The work is in fact reminiscent of the calm monumentality of Giovanni Bellini, with the explicit homage of the musician angel at the center. Despite the general admiration and the resonance, the painting aroused a little influence among the Venetian artists, certainly less than the artist’s etchings.

Leonardo and Leonardeschi in Laguna

Leonardo da Vinci visited Venice in 1500 and perhaps he had already been following Verrocchio in 1496. Although his works created or left in the lagoon city are certainly not identifiable, many clues and iconographic and stylistic quotations confirm that his passage was not unobserved, contributing fundamentally to the birth of tonalism, an extreme consequence of the nuance, and the spread of aerial perspective.

The presence and influence of Lombard artists of Leonardesque matrix in the years immediately following is more documented. In Venice the Lombard nation met at the Scuola dei Lombardi, located in a building erected at the end of the fifteenth century at the Basilica dei Frari. From the quantitative point of view, the sculptors and the stonemasons (among which those of the Lombardo family) prevailed. From the end of the fifteenth century, however, some painters began to be present and well included, among which Andrea Solario, brother of the sculptor Cristoforo and author of small works of sacred subject, and Giovanni Agostino da Lodi, considered the first popularizer of the Leonardesque ways in Venice. The latter is responsible for the boatmen’s altarpiece for the church of San Pietro Martire in Murano.

Then came Francesco Napoletano, who died in Venice in 1501, and Marco d’Oggiono, former direct collaborator of Leonardo, who made a series of canvases for the Lombard School, now lost, which had to contribute a lot to the spread of Leonardo’s ways, especially in Giorgione.

Giorgione

Giorgione was the painter who undertook a profound renewal of the lagoon painting language, in little more than ten years of activity. Figure in many ways mysterious, with very few biographical information, was an artist perfectly integrated into the circle of aristocratic intellectuals, for whom he created some portraits and especially works of reduced size by complex allegorical meanings, today only partially decipherable.

Meditating on the Leonardesque models, he came to develop a style in which color is the master: often laid directly on the support without a precise preparatory drawing, it generates the variations of light for “spots” of color, which define the volume of the figures, the softness and relief, with chiaroscuro effects of “atmospheric winding”, ie that particular result for which the figures seem to be inextricably merged into the landscape. The inspiration of the moment thus begins to take precedence over the preparatory study.

Already in works attributed to the initial phase, such as the Benson Holy Family or the Adoration of the Allendale shepherds, a delicate chromatic draft is captured, highlighting atmospheric values and the harmony between figures and the environment. The Castelfranco Altarpiece (1502 circa) already shows an innovative structural simplification, resolving the sacred conversation, still set in a pyramidal way, in a rural background rather than an architectural one (as in the tradition of Giovanni Bellini) and without worrying about the perspective rigor (as seen in the unclear relationship between the depth of the thrones and the checkered floor). Above all the figures of the lateral saints are modeled with soft piers of light and shadow, against the background of a red parapet that divides the composition into two halves, an earthly and a “heavenly” one. In the landscape the mastery of the tonal scale of the aerial perspective seems perfect, according to which the farthest objects are lightened by the effect of the natural haze.

In the Three Philosophers (about 1504-1505) numerous allegorical elements merge, perhaps referable to a representation of the Magi as “three wise men”. The sun is setting and gives the work a warm and soft light, which accentuates the sense of suspension and mystery, in which the appearance of the star (perhaps the glow in the cave) comes to guide the cognitive research of the Magi. Equally complex, rich in stratified meanings, it is the painting of the Tempest, a magnificent example of a landscape in which allusive figures are perfectly integrated.

Works of such complexity were born in a context of very close relations between client and artist, participants in the same culture, as evidenced by a letter from Thaddeo Albano to Isabella d’Este in which the agent declares he is unable to procure a work by Giorgione to the marquise because the relative owners would not have sold them “by pretending nobody” having “made them do to want them to enjoy for them”.

The masterpiece of the last phase is the sleeping Venus, an iconographic recovery from the ancient that enjoyed a remarkable success far beyond Venice, where the relaxed and sleeping goddess, of a limpid and ideal beauty, finds subtle rhythmic chords in the landscape that dominates it.

Around 1508 Giorgione received the only public commission of which traces remain, the fresco decoration of the external façade of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, realized in collaboration with Tiziano. Only the figure of a very deteriorated Nude remains of the cycle, in which, however, there must have been multiple symbolic references and intense naturalism, which can also be found in other works referring to those years as the Old Portrait (1506).

Late activity of Giovanni Bellini

Giorgione’s example accelerated that process, which has been going on since the last two decades of the fifteenth century, to represent the depth of space through an effect of modulation of air and light, in which the figures are inserted with calm naturalness. Among the protagonists of these conquests is still the old Giovanni Bellini, in works such as the Baptism of Christ and the Madonna del Prato, but it is with later works, like the Pala di San Zaccaria which demonstrates the assimilation and the appropriating of the technique tonalistaof Giorgione. In this altarpiece the architectural structure opens on the sides on clear views of the landscape, which let a warm and clear light penetrate, which highlights the intense concentration of the figures and the chromatic richness of their garments.

A further step in the fusion between elements of the landscape and figures took place with the altarpiece of Saints Cristoforo, Girolamo and Ludovico di Tolosa for the church of San Giovanni Grisostomo, which integrates some ideas of younger masters, such as Giorgione and the Pala di Castelfranco or as Sebastiano del Piombo and his Pala di San Giovanni Crisostomo.

His fame, now vast beyond the borders of the Venetian state, is the subject of numerous requests from individuals, on rare subjects in his production, related to literature and classicism. In a letter by Pietro Bembo to Isabella d’Este (1505), we learn how the old master is fully involved in the new cultural climate, in which the artist is now active also in the thematic and iconographic elaboration of the requested subject: « the invention »writes Bembo« it will be necessary that the agreement to the imagination of him that has it to do, which has pleasure that many marked terms do not give to his style, use, as they say, to always wander to his will in the paintings ».

Among the last masterpieces is the Festino degli dei, a work that inaugurates the series of pictorial decorations of Alfonso I d’Este’s alabaster dressing room, or Noah’s Ebbrezza. A year before his death, in 1515, he signed the Young nude woman in the mirror, in which the female body is delicately modeled between the dim light of the interior and the light that emanates the open window onto a wide-ranging landscape, under the banner of a clear classicism.

The beginnings of Tiziano

At the beginning of the sixteenth century Tiziano also took his first steps, called to complete works both after the death of Giovanni Bellini (the Festino degli dei) and Giorgione (the Venus of Dresden). Around the year ten, his assimilation of Giorgione’s language was so strong that it made it extremely difficult, even today, to attribute to man or the other some works such as the Concerto campestre, almost unanimously referred to Titian although permeated with themes of Giorgione’s intellectual circles.

The style of the painter from Pieve di Cadore was soon characterized by a greater chromatic and monumental intensity of the figures, more solid and inserted in narrative contexts of easy immediacy, such as the frescoes of the Miracles of St. Anthony of Padua in the Scuola del Santo in Padua (1511). In these early works the dramatic effectiveness and a decisive scanning of space is evident.

Sebastiano del Piombo’s beginnings

The example of Giorgione was fundamental in those years for another young artist, Sebastiano Luciani, later called Sebastiano del Piombo. His pictorial debut took place between 1506 and 1507, with works linked to Giorgione’s suggestions with greater plastic and monumental prominence, such as the doors of the organ of San Bartolomeo a Rialto, or the Pala di San Giovanni Crisostomo. The latter shows a bold asymmetrical composition, with the background divided between an architectural part and a landscape opening, according to a scheme that will then be used for brilliant developments (such as Titian’s Pala Pesaro).

The beginnings of Lorenzo Lotto

More original were the first experiences of Lorenzo Lotto, active at least since 1503. In that year he was in Treviso where he painted a portrait of the bishop Bernardo de ‘Rossi, characterized by a solid plastic structure and a precise physiognomy definition, which echoed the psychological suggestions of Antonello da Messina and the sharpness of Nordic art. The custody of the painting was also painted with an allegory on the contrast between virtus and voluptas, of cryptic interpretation, as well as the covered with allegoryof an unknown portrait (Washington, circa 1505), where common allegorical motifs are juxtaposed freely, as happened, in some ways, in the composition of heraldic emblems.

Gradually his language began to deviate from current culture, by a sort of restlessness, which manifested itself both in formal choices and in content. For example, the altarpiece of Santa Cristina al Tiverone appears as a quotation from Bellini’s Pala di San Zaccaria, but it separates itself for the tighter rhythm, which brings the characters to intertwine looks and gestures with restless and varied attitudes, no longer just in the sign of serene and silent contemplation. The light is cold and incident, far from the warm and enveloping atmosphere of the tonalists.

To these resistances to the dominant motifs, the artist accompanied an opening towards a more acute realism in the rendering of details, a more pathetic sentiment and an attraction for the representation of the restless and mysterious nature, typical of Nordic artists like those of the Danubian school. Examples are such as the Mystic Wedding of Saint Catherine, the penitent Saint Jerome or the Pietà of Recanati.

The maturity of Titian

The death of Giorgione and then Bellini, the departure of Sebastiano del Piombo and Lorenzo Lotto favored, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, the unchallenged assertion of Titian on the Venetian scene. Obtained a quick fame especially with a series of portraits, in 1517 he became official painter of the Serenissima. In those years also profane subject paintings were destined for the most cultured patrons, such as the Three Ages of Man (around 1512) and the Sacred Amor and the Profane Love (about 1515).

From about 1518 it began to measure itself at a distance with the conquests of the Roman renaissance of Michelangelo and Raphael. The altarpiece of the Assumption aroused admiration but also perplexity for the decisive leap forward in style, set to grandiose and monumental dimensions, eloquent gestures, and a use of color that transmits an unprecedented energy, now far from the calm atmosphere of tonality. The fame won procured the first commissions by Italian courts, including those of Ferrara and Mantua. From about 1518 Alfonso I d’Este commissioned him a series ofBacchanalia for his study, among which Bacchus and Arianna stands out, combining classic references, dynamism and a wise use of color, chosen in the best available qualities on the Venetian emporium.

In the portraits of those years he showed an interest in making the physical presence of the protagonists, with innovative compositional and luministic cuts and non-traditional poses, under the banner of immediacy and vivacity.

The renewal promoted by Doge Andrea Gritti is revealed in works such as the Pala Pesaro, in which the fifteenth-century schemes are left behind permanently. The Madonna is in fact on a throne placed laterally, as if in the side aisle of the church, to which the altarpiece was destined, there was an opening with an altar oriented in the same direction as the greater one. Gestures and attitudes are natural, in a deliberately asymmetric and therefore more dynamic scheme.

With the friendship of Pietro Aretino, bound by relationships with numerous courts, Tiziano could accentuate the entrepreneurial character of his activity, becoming one of the richest and most requested artists of the peninsula.

Pordenone

With Palma il Vecchio defunct in strict observance role “tizianesca”, the only painter able to deal with Tiziano on the Venetian scene in the twenties / thirties is the Friulian Pordenone. His training was inspired by Mantegna, by the engravings of Dürer and the other Nordic masters and had culminated with a trip to Rome in 1514 – 1515 when he had come into contact with the works of Michelangelo and Raphael. Thus he developed a magniloquent style, balanced between classical memories and popular narration.

His specialty was the large cycles of frescoes, such as those in the cathedral of Treviso, in the church of Madonna di Campagna in Piacenza, in the church of San Francesco in Cortemaggiore and above all in the Duomo of Cremona. Here his style shows a representation at the same time discursive and solemn, with a remarkable perspective virtuosity.

The altarpieces are more discontinuous: if in those destined to the province the tone remains magniloquent, those for Venice appear too cumbersome, tied to forcing perhaps due to the anxiety of not disappointing the buyers.

With his death in Ferrara, in some mysterious ways, the confrontation with Titian ended and his work systematically passed into silence in the subsequent Venetian artistic literature.

Source from Wikipedia